Revista Internacional de Educación y Análisis Social Crítico Mañé, Ferrer & Swartz.

ISSN: 2990-0476

Vol. 3 Núm. 2 (2025)

The Antifascist Education International (AfEI)

Internacional Antifascista de Educación (IAdE)

Internacional Antifascista de Educação (IAdE)

Enrique-Javier Díez-Gutiérrez

Catedrático en la Universidad de León. España

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3399-5318

enrique.diez@unileon.es

Manuel Fernández Navas

Profesor Titular en la Universidad de Málaga. España

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5296-5248

mfernandez1@uma.es

Maria Patricia Angulo Soto

Directora Grupo de Estudios Avanzados por las Infancias Vulneradas

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6437-6347

mpases@yahoo.es

Enrique Berjano Zanón

Catedrático en la Universitat Politècnica de València. España

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3247-2665

eberjano@upv.es

Abstract

The Antifascist Education International emerges as a global network of individuals, organizations, and institutions engaged in teaching, research, and educational practice, united by a commitment to public, democratic, and anti-fascist education. This international network promotes critical thinking, social justice, and the defense of the right to an emancipatory education in the face of authoritarian and neoliberal discourses.

Keywords: Antifascist Pedagogy, Anticapitalist Education, Democratic Education, Inclusive Education, Pedagogy of the Common Good.

Resumen

La Internacional Antifascista de Educación nace como una red global de personas, organizaciones e instituciones dedicadas a la docencia, la investigación y la acción educativa, comprometidas con una educación pública, democrática y antifascista. Esta red internacional promueve el pensamiento crítico, la justicia social y la defensa del derecho a una educación emancipadora frente a los discursos autoritarios y neoliberales.

Palabras clave: Pedagogía Antifascista, Educación anticapitalista, Educación democrática, Educación inclusiva, Pedagogía del Bien Común.

Resumo

A Internacional Antifascista para a Educação foi fundada como uma rede global de indivíduos, organizações e instituições dedicadas ao ensino, à investigação e à ação educativa, comprometidas com uma educação pública, democrática e antifascista. Esta rede internacional promove o pensamento crítico, a justiça social e a defesa do direito a uma educação emancipadora face aos discursos autoritários e neoliberais.

Palavras-chave: Pedagogia Antifascista, Educação Anticapitalista, Educação Democrática, Educação Inclusiva, Pedagogia do Bem Comum.

Introduction

According to the 40dB survey conducted at the end of 2024 for El País and Cadena SER (Fernández-Vila, 2024), more than one in four young people, 25.9% of men between 18 to 26 years old, the so-called Generation Z, consider that authoritarianism could be preferable to democracy “under certain circumstances”. Among women, this figure decreases by eight percentage points. Strikingly, the majority of these young people who express some tolerance for authoritarian regimes appear largely unaware of the social and political events that occurred in Spain from the Civil War through to the democratic transition. This trend is also highlighted by a study undertaken in 2022 by the Instituto de Investigación Social y de Mercados (Junquera, 2022). Such lack of historical knowledge helps explain why some young people feel able to assert, with complete nonchalance, that “life was better under Franco”: “due to there was full employment and everyone worked”; that “at that time, you could easily buy a house and a car”; or that “there were fewer problems with security, and criminals [referring here to immigrants], did not enter a police station only to be promptly released”. In this narrative, the dictatorship is portrayed as an idyllic era and held up as a model for social order and peaceful coexistence (Díez-Gutiérrez, 2025).

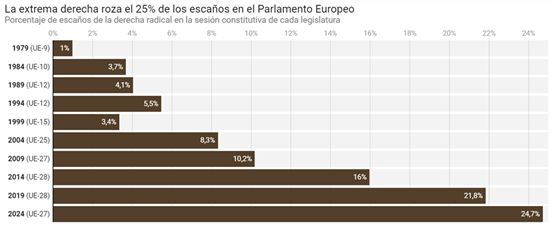

However, this phenomenon is not confined to Spain. The growth and boom of the far-right across Europe has occurred slowly but inexorably (Fariza & Torralba, 2025). Whereas far-right Members in the European Parliament (MEPs) accounted for only 8.7% twenty years ago, this proportion has increased steadily following the elections of 2009 (11.8%), 2014 (15.7%), and 2019 (18%). After the elections of June 2024, the far-right expanded its presence to nearly 25 % of the European Parliament, which means that almost one in four MEPs now belongs to a far-right party. These far-right parties, in their various forms, have increased their number of seats in 16 of the 27 member states and have only lost ground in three. Compared with the previous Parliament, the far-right has gained 48 seats, an increase of almost 37%. Although the far-right is divided into three groups within the European Parliament, it has nonetheless become the second most-voted political force in Europe, ahead of the social democrats.

Figure 1.

Percentage of seats held by the radical right in the European Union. (Spanish version)

Source: European Parliament (Flores, 2024).

The same trend can be observed in much of the Americas. The victory of Daniel Noboa in the April 2025 presidential elections in Ecuador further fuels the rise of right-wing and far-right governments in Latin America in recent years, embodied by eccentric and radically libertarian figures such as Nayib Bukele, José Antonio Kast, and Javier Milei, and an unnuanced political alignment with the neofascism of Donald Trump in the United States. Javier Milei, far-right, supremacist and misogynistic politician, was the most voted-for presidential candidate in Argentina (30%) and is currently implementing an ultra-neoliberal and neo-fascist platform in the country “with ruthless determination”. Likewise, Republican Party of Chile, led by José Antonio Kast, a far-right party, won a sweeping victory in the 2023 elections to the Constitutional Council and appears likely to govern in 2026. Similarly, the far-right leader Jair Bolsonaro lost the most recent Brazilian presidential elections by a narrow margin, despite having previously managed a pandemic, largely from a position of denialism, which caused the death of 700,000 people. And finally, there is Donald Trump, a businessman convicted of 34 offences, who returned to the presidency of the United States in 2025, despite his conviction and his indictment in three additional cases involving a total of 48 charges.

To this can be added the cases of Rodrigo Duterte, former President of the Philippines, in Southeast Asia, who openly acknowledged leading “death squads” and employing “extrajudicial killings” to combat crime, leaving behind a weakened democracy, a terrorized population, and between 12,000 and 30,000 deaths resulting from his so-called “war on drugs” which is now continued under the leadership of the son of the former dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Similarly, the President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, whose victory in the 2024 elections has reinforced his approach to crime through systematic state violence, the militarization of public security, and arbitrary arrests and mass incarceration as primary strategies, is notable. His expedited constitutional reform in August 2025 will permit indefinite reelection, thereby consolidating his authoritarian project in El Salvador.

All this reflects a progressive far-right shift in Western policies, which increasingly adopt many of the demands of the far-right parties, such as closing borders and restricting the right to asylum, rolling back some of the most advanced measures to combat the climate crisis, and promoting a bellicose agenda. An example of the latter is the European Union, which has announced plans to spend €800 billion on purchasing weapons from the United States, ostensibly to stimulate its economy, and to supply them to Ukraine in order to sustain the war against Russia (Kamenova, 2024).

Educational neofascism

All these authoritarian groups have managed to shape a narrative aimed at defining and establishing educational policies that govern formal education systems, but also at promoting a broader public pedagogy that reconfigures common sense and the collective vision of societies, a set of strategies and approaches that we refer to as educational neofascism.

Essentially, they seek to operate through a double strategy: on the one hand, they expand spaces for the representation of capital’s interests within administrations, schools, and educational communities, promoting various mechanisms of both exogenous and endogenous educational privatization (Ball and Youdell, 2007). On the other hand, they seek to incorporate into sector regulations the curricular content and school practices shaped by neotraditional logics: machismo, androcentrism, racism, and homophobia, as forms of control and governance at a distance, exerted through pressure and fear over different educational actors. At the same time, their cultural and ideological war is directed at confronting an alleged “conspiracy theory” organized through a supposed left-wing plot that seeks to infiltrate schools with ideological principles portrayed as dangerous to Western civilization and its traditional values. Such a plot is linked to what conservative sectors have labeled “cultural Marxism” understood as a remnant of Bolshevism that has relocated its sphere of operation to the realm of social culture more broadly, within which education becomes a strategic area.

That threat must be confronted through a return to “classical values” colored by a peculiar blend of patriotism and what they present as “patriotic machismo”. They therefore fight what they call “gender ideology” which they regard as a feminist aberration; they promote the restoration of the private sector’s agenda in education in response to what they frame as the State’s attempt to “monopolize the indoctrination of children’s minds”, and with the aim of expanding the spaces for capital reproduction, since they see the school not only as a business (for capital) and an (individual) investment, but also as a factory of human capital serving the demands of markets and corporations.

Moreover, this strategy seeks to create a “new common sense”, a social and cultural shift. It aims to open the “Overton window” we previously discussed. That is, to ensure that terms, ideas, gestures and references that were previously socially unacceptable, gradually become part of the public discussion until they are normalized and incorporated into the public agenda, eventually being debated and presented as just one more possibility among others. This is a pedagogical and educational tactic, as well as a political, communicative, and ideological one, intended to promote a form of “public pedagogy” that ultimately consolidates cultural elements accompanying processes of social change. It is part of the current cultural battle, a notion reappropriated by the far-right itself (Laje, 2022), that seeks to “re-educate society” from a reactionary standpoint.

This framework of the far-right’s “re-educational intervention” has led to narratives originating from the manosphere[1] becoming socially legitimized and to ultraconservative agendas even being translated into public policy. Furthermore, in its effort to radicalize and polarize public debate, it has sought to revive symbols previously banned from the public sphere, such as the Nazi salute, displayed by neofascist icons like Steve Bannon, Eduardo Verástegui, or Elon Musk (Cammaerts, 2025).

Therefore, rhetorical extremism has reached such a degree that Agustín Laje, one of the main intellectual figures associated with Argentina’s current president, has ended up labeling those zurdos (left-wing) as “enemies”, with all the epistemological, ideological, social, pedagogical, and political implications that such a designation involves. He has also stated that

we celebrate the police, we congratulate them; every well-placed bullet in each leftist has been, for all of us, a moment of rejoicing; every image of a zurdo whining because of pepper spray in their face has been, for us, a very pleasurable thing to watch, a moment in which we stand up and applaud. (Astillero, 2024).

Let us not forget, in light of these words, that language constitutes the horizon upon which our understanding and interpretation of the world are built, and that naming reality has a performative impact on how it is configured. As the journalist Kapuściński (2002) pointed out, wars always begin long before the first shot is heard; they actually begin with a shift in the language used by the media. This is the cultural war of the far-right, which designates as an “enemy” to be eliminated anyone who does not think as it does, employing a performative discourse that has real consequences for society and for education.

The educational strategies of global neo-fascism, both within formal educational systems and in its public pedagogy, require careful political analysis, since it is precisely in cultural and educational change that these forces have concentrated the most significant efforts of their cultural battle. This far-right strategy is far from the caricature that some sectors of the left have constructed, essentially based on the idea that “their only language is hate” or that, in general, they are incompetent or incapable people. Such left-wing intellectual laziness has allowed these groups to advance, learn from the left-wing itself, expropriate its concepts, exploit its pedagogical and communicative strategies, and now grow politically and electorally, and most importantly, consolidate their influence in the realms of culture and “common sense”.

The internationalization and transnational organization of educational Neofascism

Another characteristic of contemporary neofascism is its global organization and coordination, forming what has been called a Reactionary or Neofascist International (Díez-Gutiérrez & Jarquín-Ramírez, 2025). The far-right is no longer merely a series of isolated parties with little influence in the European Union, Latin America, or the United States; rather, it is growing and becoming increasingly organized.

The transnational cooperation of the new Latin American far-right with like-minded currents in the United States and Europe has been articulated through the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), which has already held multiple meetings with prominent participants from Argentina, the United States, Italy, Israel, El Salvador, and Hungary (Tcach, 2023). CPAC is a periodic meeting organized by the American Conservative Union (ACU) since 1974. Over time, and through a clear process of internationalization, it has gradually become a meeting point for the new right, the old right, the alt-right, and the contemporary global far-right. The event brings together world leaders aligned with this ideology, hundreds of organizations, thousands of activists, and millions of viewers through the media. Historically, it has played a key role in articulating the convergence of politicians, public intellectuals, strategists, and activists in order to build networks and merge diverse agendas. CPAC has now become a global meeting space and an almost mandatory forum for the various expressions of the global far-right. The guest list includes far-right and libertarian leaders such as José Antonio Kast, former presidential candidate in Chile; Eduardo Bolsonaro, son of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro; Santiago Abascal, leader of Vox in Spain; Ted Cruz, ultra-conservative Republican senator from Texas, United States; Steve Bannon, a well-known strategist of the US far-right, and Javier Milei, the current president of Argentina, among the most prominent. This list is further complemented, of course, by Elon Musk, who posed for a photograph with a chainsaw, like a rock star, alongside Milei.

In 2024, two crucial events took place in Madrid: the first, “Madrid Europa Viva 24” organized by Vox and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), brought together global far-right politicians, including the Argentine president Javier Milei, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, former Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, among others. The second was the regional meeting of the Atlas Network think tank, called “Europe Liberty Forum 2024”, organized by the Fundación para el Avance de la Libertad (Fundalib), a Madrid-based think tank affiliated with Atlas Network. The coincidence of these two events is indicative of the growing political-electoral organization of the far-right in both Europe and globally, forming what has been called a Reactionary or Neofascist International (Díez-Gutiérrez & Jarquín-Ramírez, 2025).

This Neofascist International has been arranged with multiple supports from think tanks such as El Yunque, the CATO Institute, the Instituto Juan de Mariana, and Atlas Network. In fact, the Atlas Network, with more than 500 partners worldwide (around one hundred in Latin America) and present in over 100 countries, supports incubators of ultra-liberal, neofascist, and libertarian ideas globally. Its annual global event, the Liberty Forum, also brings together businesspeople, economists, directors of organizations and associations, and political leaders associated with libertarianism and neofascism.

In education, this global organization of neofascism allows us to trace a set of common ideological trends that cut across the various expressions of the far-right worldwide. That is why we are talking about Neofascist International in Education. These trends include: 1) the denunciation of a leftist threat in education, sometimes framed as an effect of “cultural Marxism”; 2) a widespread rejection of educational proposals that aim to address cultural differences in schools, particularly regarding equality policies, sex education, and the critical analysis of ethnic relations; and 3) a focus on individual and family “liberty” of choice in education. Furthermore, this call for liberty is also linked to a market-oriented perspective regarding the content delivered in classrooms, which fosters an anti-government rhetoric, especially in the context of progressive or center-left governments. All of the above points converge in a project aimed at increasing control over public education by these actors, while simultaneously subjecting it to constant criticism regarding its practices, content, and outcomes.

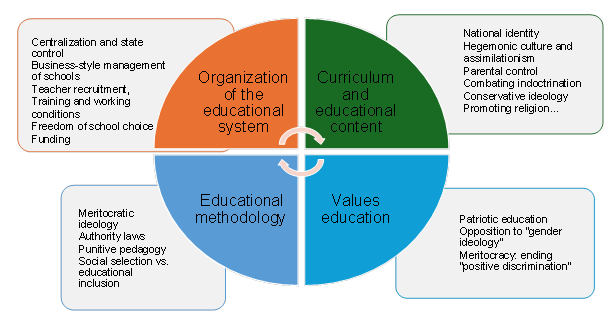

Their strategies involve organizing educational systems through centralization and state control, with the clear exception of Germany due to its history and tradition, in order to supervise textbook content and prevent teachers from taking a stance on “political, ideological, or religious matters”. Organizationally, they also believe that schools should be managed like businesses, reflecting their commitment to neoliberal ideology as a core principle of social functioning, and restoring power to men in a profession considered “overly feminized”, according to the far-right. In line with this, the far-right advocates for privatization, opening education to private enterprise as a new business opportunity, and school choice, promoting state-subsidized private schools and school voucher programs.

Regarding the curriculum and educational content, they believe that these should perpetuate and legitimize the hegemonic culture and reinforce a “patriotic” national identity through education, while opposing interculturalism and promoting a strong assimilationism that “defends the dominant culture confidently and proudly”. School content should align with their ideology, which is based on the recovery of a supposed epic past, a heroic and mythical “national identity”, tied to traditional religious, racial, and cultural values, or a combination of all these characteristics. For this reason, what is taught in pluralistic public schools must be controlled through mechanisms such as the “PIN parental” (in Spain), which allows parents to veto complementary curricular activities offered during school hours that relate to sex education, human rights education, or peace education, under the argument of “protecting minors from indoctrination” (Consejo General del Trabajo Social, 2021). In contrast, they promote a “patriotic” education that glorifies “the feats and accomplishments of national heroes” and values linked to meritocracy, demanding an end to “affirmative action”, which they claim disproportionately benefits immigrant populations.

In line with the above, they demand the recovery of a culture and ideology of effort as the foundation of educational methodology. Likewise, they promote discipline and competition among students as a central pillar for improving educational quality, which places sole responsibility for academic failure on the student. In accordance with this ideology of effort, they advocate for authority laws that “empower teachers” to enforce it. In fact, they call for acts of aggression against teaching professionals to be considered “crimes of assault on authority”, equating the role of teachers with a policing logic.

In short, we can see that, for neofascism, education “is the method”. They aim to make schools and education in general the stronghold of their ideological and cultural battle. Their intervention targets not only schools and universities, but also, and primarily, the common sense of the population through a cultural struggle at multiple levels. Paraphrasing Thatcher, one could say that for the far-right, education is the method, but the goal is to change -from a reactionary point of view—the heart and soul of societies (Beauvallet, 2015).

Figure 2

Neofascist proposals in education.

Source: Díez-Gutiérrez & Jarquín-Ramírez (2025).

The Antifascist Education International (AfEI)

As we can see, the specter of neofascism, with its hatred, intolerance, and thirst for domination, has resurged with force across educational spaces worldwide. In the face of this offensive, which seeks to segregate, silence, and subjugate, education becomes the primary battleground. We cannot remain neutral. Those of us who believe in freedom, equality, and solidarity must organize. It is for this reason that the Antifascist Education International (AfEI) was founded.

Fascism is not merely an ideology of the past: today, neofascism reemerges, disguised as reactionary populism, libertarianism, far-right, or extreme-right politics, promoting hatred and exclusionary policies that aim to turn schools and universities into sites of indoctrination, censorship, and fear. In response, we raise our voices to affirm that education is a universal, emancipatory, and deeply political right, which must be oriented toward social justice, equality, and freedom. For this reason, we join together across countries, pedagogical traditions, and social struggles to build an international network of teachers, students, families, communities, and social movements committed to the active defense of democracy, memory, and human dignity.

The Antifascist Education International (AfEI) is a global network of people dedicated to teaching, research, and educational action, committed to public, democratic, and antifascist education. We promote critical thinking, social justice, and the defense of the right to emancipatory education in the face of authoritarian and neoliberal discourses.

AIE is based on core principles articulated around four main tenets: (a) Education cannot remain neutral in the face of hatred, discrimination, or denialism: to educate is always to take a stand for life, peace, and human rights; (b) Schools must be spaces free from censorship and ideological persecution, where critical thinking, historical memory, and collective creativity can flourish; (c) Teaching is not merely a technical profession, but an ethical and political commitment to present and future generations; and (d) The struggle against contemporary neofascism requires international alliances that transcend borders and exclusionary nationalism.

Regarding its principles, they are grounded in five proposals that have allowed various critical pedagogical traditions, different geographic contexts, and diverse social, political, and educational struggles to converge:

1. Education as a political act of emancipation. We reject the false neutrality that conceals the perpetuation of injustices. True education must equip individuals with a critical thinking to analyze the world, understand its inequalities, and transform it. Education is a weapon against ignorance and fear, which are fundamental pillars of neofascism and libertarianism.

2. Against indoctrination and historical revisionism. Neofascists manipulate history to construct narratives of ethnic purity and grandeur, erasing the struggles of the oppressed and glorifying oppression. We oppose this hijacking of the past. We defend a truthful, critical, and plural historical memory that honors the victims of fascist barbarism and teaches the horrors of authoritarianism, so that they may never be repeated.

3. Public, free, secular, anti-patriarchal, inclusive, democratic, intercultural, anti-colonial, anti-neoliberal, anti-capitalist education for the common good. We defend an education committed to the common good, one that fights against machismo, LGBTIphobia, racism, animal cruelty, violence, and all forms of discrimination. An education that teaches without dogma, leaves no one behind, practices democracy radically, questions ethnocentrism, and develops a curriculum explicitly anti-neoliberal, anti-capitalist, and anti-fascist. Because to be a democrat, one must be antifascist.

4. For a pedagogy of questioning, not obedience. Fascism demands submission and dogmatism. We promote curiosity, debate, doubt, and creativity. Antifascist education fosters complex thinking, the ability to ask uncomfortable questions, and the courage to challenge all unjust authority.

5. Internationalism and anti-racism. The reproduction of oppressive class, gender, and ethnic relations lies at the core of the neo-fascist project, which constructs a narrative hostile to those who are supposedly seen as threats to Western civilization: migrants, “leftists”, and now anti-fascists. In response, we promote an education that recognizes diversity as a source of cultural and political wealth, forming the foundation for active struggle against racism, xenophobia, and aporophobia. Our aim is to cultivate an understanding that liberation is for everyone.

The Antifascist Education International (AfEI) is not merely a forum for debate. It is a call for coordinated action. The initiatives it has launched can be summarized as follows:

¾ Building a global network of mutual support, training, and coordinated action against the rise of authoritarianism, connecting educators, students, academics, intellectuals, families, and communities to share resources, methodologies, and strategies for pedagogical resistance.

¾ Promoting critical and emancipatory pedagogies that cultivate solidarity and hope.

¾ Exposing and boycotting any educational initiative, whether public or private, that promotes neo-fascist, xenophobic, sexist, homophobic, or values that condone the mistreatment of animals. Denouncing and resisting any attempt to colonize education with hatred, fear, or commodification.

¾ Developing and disseminating open educational materials (curricula, textbooks, instructional units) that reflect our anti-fascist, internationalist, and emancipatory principles.

¾ Protecting and supporting teachers and students who are persecuted for their commitment to social justice, anti-fascism, and democracy anywhere in the world.

¾ Occupying all educational spaces, from primary schools to universities, from formal education to community classrooms in local neighborhoods, and transforming them into trenches of dignity and resistance.

Around these principles and actions, the Antifascist Education International (AfEI) invites all individuals and groups who believe that another form of education is possible, that another world is possible, and who dream of a society of free, just, and equal people, to join us. The AfEI proclaims that another future is possible: a future in which schools and universities are spaces of freedom, justice, and shared dignity for the common good.

Discussion and conclusions

It is commonly said that fascism, contemporary neo-fascism in this case, must be fought both on the streets and in people’s minds. We understand that, although material conditions are strategically important to prevent its growth, the struggle to foster a collective antifascist consciousness is decisive.

For this reason, we must analyze how it is possible that so many people (many from the working class) have gone through public schools and the educational system in democratic contexts, yet in the 21st century, defend neo-fascist, patriarchal, xenophobic, aporophobic, neoliberal, and capitalist ideologies, supporting systems based on selfishness, predatory logic of the strongest, and inequality. What have we been doing in public education over the past sixty years?

We must ask ourselves what we have been doing in education all these years to account for the rise of neo-fascism in Spain, Europe, and worldwide. How is it possible that, despite establishing laws and international programs to educate in human rights, social justice, equity, solidarity, and equality, so many young people around the world are joining the trend of the far-right? Have we focused too much on technical skills in schools, dedicating most of our effort to preparing young people for the market rather than for what truly matters: the model of society, the principles, and the values by which a society for the common good should be guided? Could it be that the demands of businesses, e.g., preparing students for the 21st century with skills, bilingualism, robotics, effort, competitiveness, and success, have overshadowed the need to combat contemporary neo-fascism and to promote mutual support, cooperation, solidarity, etc.?

We need to rethink the current model of education. We need an educational system that helps build a different model of society, one in which neo-fascism and its doctrines of hatred toward others, antifeminism, anti-ecologism, and disregard for fundamental human rights are neither possible nor imaginable. A model of education based on the common good.

As Nichols & Berliner (2007) argue, we should be number one in the world in the percentage of 18-year-olds who are politically and socially engaged. Far more important than our math and science scores is the engagement of the next generation in sustaining a real democracy and building a more just society for those who need it most: young people, the sick, the elderly, the unemployed, the dispossessed, the illiterate, the hungry, and the helpless. Schools that fail to produce politically active and socially useful citizens should be identified, and their failure rates should be published in newspapers.

This requires a joint effort by families and teachers who strive to teach their children and students that the most important things are not grades or individual success, but social justice, solidarity with their peers, and the common good that enriches both the community and the planet. But it also requires the work of “the whole tribe”. Especially the media and social networks, which play a profound role in “educating” current and future generations. It is essential that the economic profit and pursuit of gain by a few no longer dictate the standards and functioning of the media, and that they instead become a service to the common good, contributing alongside the educational system to teaching human rights, solidarity, mutual support, degrowth, feminism, and all those principles and values proclaimed in international treaties and agreements but too often left unfulfilled.

We must continue moving toward an educational model that contributes to the common good of future generations and of the entire current educational and social community. A global model of education, one that involves the whole tribe, fostering the development of people who are more equal, freer, more critical, and more creative. Lucius Annaeus Seneca, in the 4th century BCE, stated: “It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare, it is because we do not dare that they are difficult” (Díez-Gutiérrez, 2022). We must dare to dream. The future of our children, of society, and of the planet as a whole is at stake.

Paulo Freire stated that “education is always a political act, as a humanistic and liberating endeavor in the struggle for emancipation” (Gijón, 2022). Therefore, as a social community, we must educate in equality, inclusion, social justice, the common good, and human rights through a pedagogy that is clearly antifascist. No compromises, no half measures. Antifascist education or barbarism, there is no neutrality possible.

Bibliography

Astillero, J. (February 5, 2024). [#VIDEO] “Cada balazo ha sido un momento de regocijo”: Agustín Laje celebra represión policial contra manifestantes argentinos e invita a cortar relaciones con gente de izquierda (por Luis Salas de Astillero Informa). Julio Astillero. https://julioastillero.com/video-cada-balazo-ha-sido-un-momento-de-regocijo-agustin-laje-celebra-represion-policial-contra-manifestantes-argentinos-e-invita-a-cortar-relaciones-con-gente-de-izquierda/

Ball, S. J. y Youdell, D. (2008). La privatización encubierta en la educación pública [Informe]. Instituto de Educación, Universidad de Londres. https://observatorioeducacion.org/sites/default/files/ball_s._y_youdell_d._2008_la_privatizacion_encubierta_en_la_educacion_publica.pdf

Beauvallet, A. (2015). Thatcherism and Education in England: A One-way Street? Observatoire de la société britannique [En ligne], 17. https://doi.org/10.4000/osb.1771

Bobric, G. (2021). The Overton Window: A tool for information warfare. ICCWS 2021 16th International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security. Academic Conferences Limited. DOI:10.34190/IWS.21.114

Cammaerts, B. (February 4, 2025). Elon Musk’s Nazi salute, George Orwell and five lessons from past anti-fascist struggles. The London School of Economics and Political Science Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2025/02/04/elon-musks-nazi-salute-george-orwell-and-five-lessons-from-past-anti-fascist-struggles/

Consejo General del Trabajo Social. (July 6, 2021). Posicionamiento sobre el pin parental: una forma de ejercer la violencia contra la infancia y la adolescencia. Consejo General del Trabajo Social. https://www.cgtrabajosocial.es/noticias/posicionamiento-sobre-el-pin-parental-una-forma-de-ejercer-la-violencia-contra-la-infancia-y-la-adolescencia/7282/view#:~:text=Posicionamiento%20sobre%20el%20pin%20parental:%20una%20forma,Portal%20del%20Consejo%20General%20del%20Trabajo%20Social.

Díez-Gutiérrez, E. J. (May 31, 2022). Pedagogía antifascista o barbarie. El Salto. https://www.elsaltodiario.com/el-rumor-de-las-multitudes/pedagogia-antifascista-o-barbarie

Díez-Gutiérrez, E. J. (2025). Pedagogía Antifascista. Octaedro. https://doi.org/10.36006/09120-4

Díez-Gutiérrez, E. J. & Jarquín-Ramírez, M. R. (February 20, 2025). La batalla cultural de la extrema derecha para “re-educar” Europa. Fundación Bofill. https://fundaciobofill.cat/es/blog/la-batalla-cultural-de-la-extrema-derecha-para-re-educar-europa

Fariza, I. & Torralba, C. (November 1, 2025). La extrema derecha mantiene uno de cada tres gobiernos europeos pese al varapalo de Wilders en los Países Bajos. El País. https://elpais.com/internacional/2025-11-01/la-extrema-derecha-mantiene-uno-de-cada-tres-gobiernos-europeos-pese-al-varapalo-de-wilders-en-los-paises-bajos.html

Fernández-Vila, A. (September 2, 2024). La mayoría de los españoles cree que la democracia se está deteriorando y su apoyo cae entre las generaciones más jóvenes. Cadena Ser. https://cadenaser.com/nacional/2024/09/02/la-mayoria-de-los-espanoles-cree-que-la-democracia-se-esta-deteriorando-y-su-apoyo-cae-entre-las-generaciones-mas-jovenes-cadena-ser/

Flores, D. (June 10, 2024). La extrema derecha crece hasta rozar el 25% de los escaños del Parlamento Europeo, pero no será decisiva. RTVE.es https://acortar.link/sgj5Zi

Gijón, R. (September 23, 2022). Enrique Javier Díez Gutiérrez: “No se puede ser demócrata sin ser antifascista.” El Salto. https://www.elsaltodiario.com/educacion/entrevista-enrique-javier-diez-gutierrez-pedagogia-antifascista

Junquera, N. (September 25, 2022). Las lagunas de los jóvenes sobre memoria democrática: La Guerra Civil fue porque el pueblo se rebeló contra Franco. El País. https://elpais.com/espana/2022-09-25/el-franquismo-un-crater-de-conocimiento-entre-los-jovenes-de-la-confusion-a-la-relativizacion-del-golpe.html

Kamenova, V. (2024). The road to European parliament mandate for populist radical-right parties: Selecting the ‘perfect’ AfD candidate. Party Politics, 30(4), 678-690. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231173804

Kapuściński, R. (2002). Los cínicos no sirven para este oficio. Anagrama.

Laje, A. (2022). La batalla cultural: Reflexiones críticas para una Nueva Derecha. Harper Collins.

Nichols, S. L., & Berliner, D. C. (2007). Collateral damage: How high-stakes testing corrupts America's schools. Harvard Education Press.

Ramos, M. (2022). Antifascistas. Capitán Swing Libros.

Tcach, C. (2023). Los nuevos rostros de la derecha. Estudios - Centro de Estudios Avanzados. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, (49), 9-11. https://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1852-15682023000100001&lng=es&tlng=es