From Drug Problem to drug-related issue. For a coherent conceptualisation in the field of addictions

De problema de drogas a problemática en drogas. Por una conceptualización coherente en el ámbito de las adicciones

Do problema das drogas ao problemático das drogas. Para uma conceituação coerente no campo das dependências

Diego Fernández Piedra

Universidad Complutense de Madrid (EGECO). Energy Control

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3138-9827

Patricia Hontoria Zaidi

Qualitative Research Analyst en Grupo AEI

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4699-6476

Jordi Navarro López

Energy Control

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3334-0741

investigacion@energycontrol.org

Claudio Vidal Giné

Energy Control. Asociación Bienestar y Desarrollo

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4936-007X

claudiovidal@energycontrol.org

Berta de la Vega Moreno

Energy Control

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8156-0207

bvega@energycontrol.org

Abstract

This article analyses the need for a consistent conceptualisation of the drug use phenomenon, moving away from reductionist and deterministic views. It argues that hegemonic conceptions, both prohibitionist and medical, have biased the understanding of the phenomenon, leaving aside cultural and social factors, proposing a holistic approach based on risk reduction. For the study, a critical analysis of the explanatory models of addictions was carried out, reviewing their historical and conceptual evolution, contrasting biomedical and psychosocial perspectives, and highlighting the role of programmes such as Energy Control in the implementation of alternative strategies. The results relate to how traditional models (penal and medical) have stigmatised substance use, leading to ineffective policies. The importance of considering the person-substance-context triangle to understand the phenomenon was noted. It became evident that approaches such as harm reduction offer more inclusive and effective strategies. For this reason, we can conclude that it is necessary to overcome hegemonic paradigms and adopt integrative perspectives that enable a comprehensive understanding of drug use in its social, cultural, and economic complexity, where risk reduction is presented as a viable and humanised approach to address this reality.

Key-words: Drugs, Health Education, Health policy, Drug policy, Health, Value systems, Social Control.

Resumen

Este artículo analiza la necesidad de una conceptualización coherente sobre el fenómeno de las drogas, alejándose de visiones reduccionistas y deterministas. En él, se argumenta que las concepciones hegemónicas, tanto prohibicionistas como médicas, han sesgado la comprensión del fenómeno, dejando de lado factores culturales y sociales, proponiendo un enfoque holístico basado en la reducción de riesgos. Para el estudio, se realizó un análisis crítico de los modelos explicativos de las adicciones, revisando su evolución histórica y conceptual, contrastando perspectivas biomédicas y psicosociales, destacando el papel de programas como Energy Control en la implementación de estrategias alternativas. Los resultados están relacionados en cómo los modelos tradicionales (penal y médico) han estigmatizado el consumo de sustancias, generando políticas ineficaces. Se constató la importancia de considerar el triángulo persona-sustancia-contexto para comprender el fenómeno. Se evidenció que enfoques como la reducción de daños ofrecen estrategias más inclusivas y efectivas. Por esta razón, podemos concluir que es necesario superar los paradigmas hegemónicos, y adoptar perspectivas integradoras, que permitan comprender el consumo de drogas desde su complejidad social, cultural y económica, donde la reducción de riesgos se presenta como un enfoque viable y humanizado para abordar esta realidad.

Palabras clave: Drogas, Educación Sanitaria, Política de la salud, Política sobre drogas, Salud, Sistemas de valores, Control Social.

Resumo

Este artigo discute a necessidade de uma concetualização coerente do fenómeno da droga, afastando-se de visões reducionistas e deterministas. Argumenta-se que as concepções hegemónicas, tanto proibicionistas como médicas, têm enviesado a compreensão do fenómeno, deixando de lado os factores culturais e sociais, propondo-se uma abordagem holística baseada na redução de riscos. Para o estudo, foi realizada uma análise crítica dos modelos explicativos das dependências, revendo a sua evolução histórica e concetual, contrastando as perspectivas biomédica e psicossocial, destacando o papel de programas como o Energy Control na implementação de estratégias alternativas. Os resultados mostram como os modelos tradicionais (criminal e médico) estigmatizaram o consumo de substâncias, gerando políticas ineficazes. Foi salientada a importância de considerar o triângulo pessoa-substância-contexto para compreender o fenómeno. Abordagens como a redução de danos mostraram oferecer estratégias mais inclusivas e eficazes..Por esta razão, podemos concluir que é necessário ultrapassar paradigmas hegemónicos e adotar perspectivas integradoras que permitam compreender o consumo de drogas a partir da sua complexidade social, cultural e económica, onde a redução de riscos se apresenta como uma abordagem viável e humanizada para fazer face a esta realidade.

Palavras-chave: Droga, Educação em Saúde, Política de Saúde, Política de drogas, Saúde, Sistemas de valores, Controlo Social.

Introduction

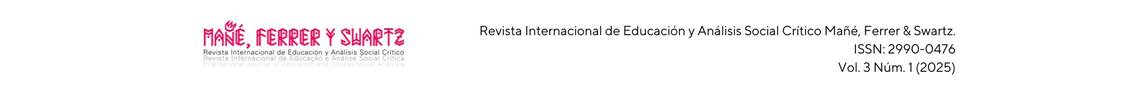

The use of psychoactive substances has been a constant in several cultures and eras, with examples ranging from the use of hemp by the Amerindian cultures, opium in the Chinese region, and wine in Ancient Greece and Egypt… among others (Escohotado 1999). However, history also reveals how some of these substances, initially promoted as miraculous, have later become serious social problems (Escohotado, 1994). Cocaine and heroin are paradigmatic examples of this phenomenon. Who could forget that, in the beginning, heroin and cocaine were introduced as miracle remedies for several ailments (Figure 1), only to be rejected and stigmatised later? (Freud, 1974)

Figure 1

Cocaine drops for toothache, 1885 advertisement.

Note. Taken from Wikimedia Commons.

In this sense, cocaine and heroin illustrate how the public perception, the stigma and the way in which society relates to some substances may change, due to more complex interests that go beyond the field of public health (Escohotado, 1997). These interests may include political, economic and social factors that influence how substances are approached and perceived, potentially leading to their stigmatisation or medicalisation.

According to the 2024 World Drug Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), drug use reached a historical record, with 292 million people using substances in 2022 (Figure 2). This represents a 20% increase compared to the previous decade, meaning an increasing global issue (UNODC, 2024)

Figure 2.

Key figures on psychoactive substance use in Europe.

Note. Taken from UNODC (2023).

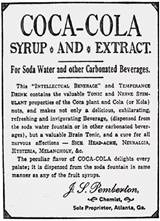

In the daily life of many societies, the use of psychoactive substances is a common practice. Examples such as coffee, which helps us wake up, nicotine, which provides a sense of energy, a glass of wine commonly associated with relaxation at the end of the day, or even the medicines used for sleep or pain relief, follow the same logical process: to resort to chemical substances to change our physical or mental condition. In other words, many of the substances considered drugs are part of our daily lives, as exemplified by the most popular cola beverage of our time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cola beverage advertisement, 1903.

Note. Taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Upon its release to the market, this beverage was promoted as a remedy for headaches, formulated with coca leaf extract and kola nuts. Over time, coca was replaced by caffeine, although its inclusion in the drink did not produce any psychoactive effects (Fundación por un Mundo Libre de Drogas, 2025). The main reason for this change was the increasing social pressure of the time, built on the growing stigmatisation of cocaine (Kahn, 1960).

This process of normalising/prohibiting substance use is linked to what Romaní (2004) described as a social fact of identity. This concept means that substance use should not be seen as an individual problem, but as part of the social structure that has integrated such practices into daily dynamics (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Coffee advertising.

Note. Taken from Espí, G. (30 October, 2024). ¡Buenos días con café! 100 frases bonitas para amanecer con energía. InStyle. https://www.instyle.es/lifestyle/100-frases-bonitas-para-amanecer-energia_64986

For this reason, the use of psychoactive substances, far from being an isolated or pathological issue, is a reflection of the rules and values of a society that has integrated them into its routines without question. This phenomenon is not only related to the reasons that drive people to use them, in search of pleasure, stress relief or adaptation to a specific social environment, but also to the denial of their existence, the stigma and the prosecution faced both by the substances themselves and by those who use them. As a result, in many cases, the risks associated with such use are often minimised or overlooked, while society maintains an ambiguous and contradictory stance towards these substances.

Nowadays, this kind of use cannot be understood solely from a medical perspective, a field to which it is often confined, but must instead be seen as a phenomenon embedded within a global and multicultural context influenced by extreme capitalism. The use of these substances has evolved and extended beyond traditional boundaries, giving rise to new ways of use, social actors, and markets. In order to understand this phenomenon accurately, we must consider not only how it affects people, but also what meaning it holds for them and for the social groups in their daily lives. This approach shifts the way we view the problem: it is no longer an individual and marginal issue, and becomes instead a complex and dynamic practice that reflects several psychosocial dynamics, as sociocultural rules, stigma, social inequality, illegal markets, and the search for identity, among others.

Despite prohibitionist policies, awareness campaigns, and imposed sanctions, drug use remains a persistent issue in many societies. This fact suggests that public policies and explanatory models on addictions are not effective to address the complexity of the phenomenon nowadays, as they perpetuate a simplistic and stigmatising approach, based on moralising language that will remain deeply rooted unless critically examined (Kiepek, 2024).

In this context, it is important to highlight the contribution of intervention programmes such as Energy Control, which operate from a pleasure and risk management approach in an effort to shift the dominant view already outlined. These programmes integrally address drug use, considering not only the effects of these substances on the body, but also the social, cultural, psychological, and economic factors that influence their use.

Everything stated so far has been necessary to make a review of the dominant conceptualisation within the field of addictions, overcoming simplistic and deterministic approaches to promote a more complete and accurate understanding aligned with social reality. To this end, a critical analysis of explanatory models of addictions has been carried out, evaluating their historical and conceptual evolution, and comparing different perspectives to achieve higher effectiveness in this field through the incorporation of a holistic view.

Methodology

This article is based on descriptive research, aimed at clarifying the existing information and verifying the accuracy of previous descriptions linked to addiction (Yuni and Urbano, 2014). It is carried out from a qualitative approach, as we start from a specific reality to discover that has been constructed and interpreted through a description and understanding of its phenomena. This situation allows the capture of the theoretical and methodological constructs of our object of study through the collection and critical analysis of relevant scientific works (Hernández et al., 2014). Unlike quantitative approaches, which focus on the measurement and statistical analysis of variables, the qualitative method allows for the exploration of complex phenomena through detailed description, interpretation, and the identification of their underlying patterns.

The choice of documentary review as a methodological strategy addresses the need to explore, organise and critically analyse the available scientific literature on addictions. This methodology enables the systematisation and comparison of diverse theories, models, and intervention approaches that are essential to understand such a complex and multidimensional field. Besides, this methodology facilitates reflection on historical developments, conceptual divergences and empirical advances in the biomedical and psychosocial models, while also allowing for the identification of alternatives that challenge prevailing paradigms. Addressing an area of study that has evolved meaningfully over time provides a global vision that could hardly be obtained through other research methods. This strategy is also specifically useful to detect gaps in the existing literature, to compare several theoretical perspectives and to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions applied in the context of addictions.

The process of documentary review and analysis was carried out through a systematic research of academic literature in specialised scientific databases. Scientific articles, books, and key theoretical reviews on addiction were selected based on criteria ensuring their relevance to the central topic, reliability of the sources, and the theoretical approach adopted. In this way, it was guaranteed that the studies addressed both current biomedical and psychosocial models. Once the information had been collected, a reflective analysis was undertaken to contrast the different theoretical perspectives and assess the effects of the proposed interventions.

This study has several limitations, among which the selection bias characteristic of documentary review is particularly notable. Given that access to sources is determined by academic databases and publications available, it is possible that relevant studies might have been excluded, especially those that are not openly available or published in less accessible languages or contexts.

Results

To understand the phenomenon of addictions and respond effectively to such a complex social reality, it is crucial to question the concepts and terms used. We cannot allow ourselves to be guided by preconceived notions, stereotypes or dominant discourses, whether derived from popular wisdom or hegemonic explanatory models. Therefore, we must critically analyse the terminology used before researching or intervening in this field to avoid the reproduction of stigmas and prejudices that could distort the understanding. Although this process may appear basic, it is essential in such a complex and marked by stigmatisation field. This is reflected in studies that extrapolate chemical reactions to the complexity of human behaviour, overlooking the fact that people who use drugs are complex beings, with multiple dimensions that go far beyond the biological field. Therefore, the uncritical use of concepts in the field of addiction enforces the hegemonic narratives that perpetuate mistakes and reduce the effectiveness of interventions.

Addiction and its study constitute a total social fact, involving historical, political, cultural, and social factors (Mauss, 2010). This means that they cannot be analysed in isolation or reduced to a single dimension, as they are embedded in a web of meanings and practices that vary according to the specific context. In order to understand them, an integral analysis that takes into consideration these multiple influences and generates knowledge that accurately reflects reality is required. (Santos et al., 2020). This understanding, as a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, leads us to think about how they can be perceived in a contradictory way, depending on the context in which they are examined. Understanding these dynamics allows us to question the rigidity of such classifications and move towards a more critical and contextualised perspective.

Psychoactive substance, pharmaceutical, medicine and drug: a great confusion

The main conceptual reference in this field currently is the World Health Organisation (WHO), which initially defined psychoactive substance as any substance that alters the function of the central nervous system after being introduced into the body (Kramer y Cameron, 1975). That is, any molecule with effects on the individual, regardless of its psychosocial context. This concept is deliberately broad, encompassing both substances used in the treatment of diseases and others with pharmacological activity. This meaning, although the scientific community considers it vague, has become a terminological standard, creating confusion by defining different realities within this phenomenon.

The matter gets even more complicated when considering the term pharmaceutical in this conceptual equation. Originally, it was associated with purification due to its connection with religion, but over time, its meaning expanded to any substance, natural or synthetic, that could improve health or treat diseases (Herrero, 2019). Later on, the WHO redefined the term as any substance that could modify one or more functions of the organism after its administration (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 1970).

Although they are often used as synonyms, pharmaceutical and psychoactive substances have significant differences between them. The pharmaceuticals specifically affect the central nervous system, while the second ones do not act only on it. For example, anxiolytics and antidepressant substances are pharmaceuticals with psychoactive power, but not all of them, as antibiotics and anti-inflammatories. In the same way, not all psychoactive substances are pharmaceuticals, as is the case with cocaine or cannabis.

The World Health Organisation (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 1966) defines medicine as a substance or combination of substances that modifies or explores a physiological or pathological system for therapeutic purposes. In Spain, the Real Decreto 1/2015, of 24th July, which approves the consolidated text of the Law on guarantees and rational use of medicines and healthcare products, medicine is defined as a compound that prevents, treats, or diagnoses diseases in humans by restoring, correcting, or modifying physiological functions. The key difference lies in the fact that medicine is a product that contains one or more pharmaceuticals and is specifically used to treat or prevent diseases, whereas a pharmaceutical is a substance that produces an effect on the body, regardless of its purpose.

The term drug comes from the Dutch droge or droghe vate, which was historically applied to barrels containing dried products with medicinal properties in the Middle Ages. In Spain, according to Ley 5/2002, of 27th June, of Measures for health protection of people in relation to the use of tobacco products, a drug is defined as any substance that modifies organic functions, generates dependence, modifies behaviour, and causes harmful effects on health and social well-being. The difference with medicine lies in its intended purpose and its regulation, reflecting a psychosocial construction influenced by ideological, political, economic, and cultural factors (Fericgla, 2000). This is why the definition of drug is inherently complex, because what may be considered a drug in one context may not be perceived as such in another.

According to Menéndez (1984), for over a century, a paradigm of scientific intervention has been consolidated and legitimised socially and culturally: the Hegemonic Medical Model (HMM). This model interprets a series of symptoms as signs of illness, recognised both by the person who feels them and by their social network. In response, expert intervention is sought to determine a treatment aimed at eliminating the symptoms and restoring health, also prescribing what should be taken to facilitate the transition and demonising all that is not used for that purpose.

An example of this phenomenon is methadone. If prescribed by a professional and used according to precise indications, it is considered a pharmaceutical. However, if purchased on the black market or used on one’s initiative, it is labelled as a drug. This distinction is understood in a process of medicalisation that extends medical control and treatment to increasingly broader aspects of personal and social life (Menéndez, 1984). In the field of addictions, this divides substances into pharmaceuticals and drugs, legitimising the former and stigmatising the latter. Most of the problems we have to define drugs scientifically arise when we rely exclusively on pharmacological criteria, ignoring social, economic and cultural factors (Comas, 1985). This approach underlines only the effects of the substance on individuals, reinforcing its association with dangerousness. Therefore, to have a more comprehensive understanding, it is essential to consider the dynamic relationship between person, substance and context, where several variables come into play. Thus, we can identify not only the effects but also the meanings that substances acquire within different cultural settings, without falling into reductionism and highlighting the importance of the psychosocial factor in the phenomenon, while keeping in view the hegemonic medical model (Menéndez y Di Pardo, 2004).

In this context, it is thus more appropriate to define drug as a chemical substance which, upon entering the body, alters one or more functions, and whose effects, consequences and uses cannot be analysed solely from a pharmacological perspective but rather within the social and cultural framework of the groups that use them (Romaní, 2004). This perspective enables us to evidence how, under the HMM, the regulation of these substances is not only driven by scientific criteria, but also by political and economic interests that establish what is considered medicine and what is labelled as a drug.

The four categories analysed are all influenced by social, political and economic factors, which affect their meaning and regulation. This also shapes the perception of the substances and the intervention strategies, reinforcing the medicalisation of some practices and the criminalisation of others. Understanding these dynamics, as well as questioning the criminalisation, enables us not only to challenge the rigidity of these classifications and adopt a more critical and contextualised perspective but also to portray the reality of drugs differently (Fraser, 2024).

From dependence to the relationship of dependence

The definitions presented so far are not based only on pharmacologic criteria. They are also influenced by the dominant medical model. Similarly, concepts such as addiction have been shaped by this approach, requiring that we reconsider them from broader perspectives, as will be explored later.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Louis Lewin proposed a conceptual framework to study drugs and their effects, unifying the existing terminology in this field. However, his approach prioritised the pharmacological aspects, attributing specific properties and consequences for each substance based on its pharmacodynamics profile, without considering the psychosocial factors (Lewin, 2009). This man classified substances into five categories: euphoriants, hallucinogens, inebriants, hypnotics, and stimulants. His proposal was based on the idea that each substance produced a characteristic and uniform effect in all individuals. A premise that, as we will discuss further in this article, is incorrect because it does not take into account the rest of the variables that influence the experience of its use.

Lewin (2009) proposed that the main motivation to use drugs lies in the pursuit of a characteristic effect. For this effect to be produced, a group of individuals that perceive it similarly must exist, regardless of the context. Thus, the motivation to use the substance lies in the desire to experience its effects, implying that use can be more or less conscious. With frequent use, this pursuit progressively leads to the emergence of three phenomena: tolerance, that appears when the person needs bigger doses to achieve the same effects due to the body’s adaptation; dependence, understood as the physical or psychological need to use the substance to avoid the effects of withdrawal and experience its desired effects; and the abstinence syndrome, referring to a set of physical and psychological symptoms that occur when the use of the substance is withdrawn (Koob y Volkow, 2010). Despite its limitations, acknowledging this author as a pioneer in this field is crucial, who warned of the risks of substance use and opposed the ideas of other academics as Freud (1974), who defended its benefits.

These concepts were not only broadly accepted at the time, but they continue to be the dominant explanatory framework in the field of addictions as it can be observed in the definitions given by the American Psychiatric Association (2002), which describes addiction as a behavioural pattern characterized by prioritising drug use over other daily activities, the emergence of withdrawal symptoms upon deprivation and an inability to control intake. Similarly, the WHO currently describes dependence as a psychic and sometimes physical state caused by the interaction between a body and a pharmaceutical, characterized by behavioural changes and an uncontrollable urge to use the pharmaceutical to experience its psychological effects and prevent the uneasiness of deprivation, either accompanied of tolerance or not (Kramer y Cameron, 1975). These conceptualisations, based on Lewin’s ideas, focus only on the pharmacological component, without taking into account that the effects of the substances depend on three factors: dosage, presentation and purity; individual and social conditions of use; and the user’s expectation, all of which are mediated by cultural rules that determine how and when use them, variables that are influenced by the psychosocial context of the individual (Comas, 1985). Because of that, as Menéndez and Di Pardo (2004) argue, it is increasingly difficult to sustain exclusively biomedical definitions, as the development of substance-related problems depends on the interaction between individual factors, personal history, sociocultural environment, and pharmacodynamic characteristics.

In this same vein, Zinberg (1984) broadened this reductionist perspective by proposing an integrated approach that considers three interrelated elements: the substance with its effects on the body; the individual, with their sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics; and the setting. This approach reinforces the idea that addictions cannot be analysed without considering the context and individual particularities, which explains the diversity of uses, effects, and consequences depending on the sociocultural environment. From this standpoint, dependence is not only a pharmacological issue, but also a social phenomenon that may operate as a mechanism of control. An example of this is the difference between the prohibition of substances like cocaine or heroin and the tolerance of alcohol and tobacco. This distinction is not only based on scientific criteria, but also on social constructs that determine what is considered dependence, how it is produced and the way to address it. This highlights the role of such discourses in ideological regulation and in the management of certain behaviours within the society.

The current use of the category of dependence is problematic, as it involves a complex interaction of social, cultural, biological and psychological factors. Although it originally was referred to substances, its application has extended to other practices as gambling, sex, the use of the internet or work, and this has been the reason why this term is used in an imprecise and diffuse manner. In many cases, the indicators of dependence respond to dominant social factors, instead of searching for effective solutions to the problems involved. In fact, the use of the own category seems to be more focused on the development of social control mechanisms, whereby certain behaviours are labelled as dependence to allow them to be regulated (Menéndez y Di Pardo, 2004).

We propose using a more open and complex terminology to describe the phenomenon of addictions, as suggested by Pallarés (1996). Instead of speaking about addition, we recommend using the term relationship of dependence to describe the process experienced by a person who regularly uses a substance in a way that is central to their life. This allows us to distinguish between different types of relationships with substances, such as experimental or psychoanalytical. Moreover, Pallarés explains that only a small proportion of people who use drugs will go on to develop dependence, making it essential to understand the bond with substances as a trajectory with different possibilities. This approach moves away from the traditional definition of dependence, dominated by the medical and biological paradigm, and proposes a more nuanced and dynamic view that takes into account the user’s context and their interaction with the social and cultural environment.

Limitations of the dominant models in the understanding of addictions

The incorporation of the concept of relationship of dependence enhances our understanding of addictions, while also underlying the limitations of the traditional biomedical models. Given that addictions are influenced by a complex interaction of psychosocial variables, it is essential for several disciplines to collaborate in creating explanatory models, avoiding this way any kind of reductionism and addressing the phenomenon in a more integral manner.

Kuhn (1992) defined a model as a representation or conceptual framework used within a scientific discipline to understand, explain, and predict phenomena in a specific field. Furthermore, he introduced the concept of paradigm, a prevailing concept in a discipline at a given time, with a set of practices, theories and assumptions that hegemonically guide research, problem-solving, and explanations within a scientific community. Bandura (1987) added that these are closed and consistent systems of discourses, hierarchical rules, forms of action, and processes of institutionalisation.

Among the various possibilities, in the field of addictions, the so-called intervention model predominates, which focuses on proposing practical courses of action in response to the specific phenomenon (Heinich, 1975). This way of action provides a detailed view of the process, specifying how, upon whom, from where, and when it should act. In this sense, what is defined as a model not only establishes how to understand addictions, but also the required conditions to be considered part of that categorisation and, in due course, to abandon that label. Furthermore, it establishes key aspects as who are the qualified professionals to intervene and make decisions, what is the role of the public administration in the management of funding, plans, and programmes, and how language is used in this field (Comas, 2010). For this reason, we consider it of utmost importance to reflect on the most relevant models that, in our context, influence the configuration of the phenomenon of addictions. According to Romaní (2004), these include:

● The penal model, characterised by a punitive approach based on laws and regulations that link the effects of substances in the body with death, aiming to eradicate the use of what is defined as drugs. In this model, drug use becomes a criminal offence, and the user is labelled as a criminal, leading to the creation of a black market with consequences such as increased delinquency, poor quality substances, and the enrichment of a few.

● The medical one, which interprets individuals who use drugs as sick rather than criminals, seeing them as subjects to be treated, diagnosed, and integrated into medical systems like any other patient, influenced by the process of medicalisation. This approach became the main reference to explain the use of the term drugs, based solely on biomedical criteria. Thus, users shift from being perceived as criminals to being considered as sick, which helped to mitigate some of the marginality associated with this phenomenon, although without eradicating it entirely.

These hegemonic models of addictions have had a great impact in the current field, but their medical-legal reductionist approach is insufficient. In the face of this limitation, Apud and Romaní (2016) emphasise the importance of the biopsychosocial model, which seeks to integrate medical, social, and psychological variables from a multifactorial perspective. This approach allows for more effective intervention in everyday life by addressing the addiction phenomenon from a systemic perspective. However, its development is hampered by the persistence of traditional approaches deeply rooted in society, which prioritise the legal and medical perspectives over psychosocial ones. According to Pons (2008), these models are being replaced by new ways of understanding addictions, promoting alternative care strategies such as:

● The risk and harm reduction, which seeks to minimise the adverse consequences of drug use in individuals with normalised use patterns and socially perceived as negative.

● The socio-ecological model, which analyses the complex interrelations between the organic, behavioural, and environmental systems.

● The use distribution, which examines the supply and availability of substances within a population or in the society as a whole.

In this context of transition towards more comprehensive approaches, the pleasure and risk management model emerges with significant force and is being presented as an innovative proposal. It seeks to balance the risks associated with use with the recognition that many people are capable of managing their use experiences in an informed and responsible manner (Martínez y Pallarés, 2013). By integrating principles of harm and risk reduction into the model, as Pinzón (2023) notes, it adds an objective dimension to the subjective aspect focused on the pleasures sought, thereby broadening its perspective.

In Spain, Energy Control stands out as one of the leading programmes applying this approach in the context of people who use drugs in leisure spaces (Fernández et al., 2024). Unlike other approaches, this program considers that drug use is not only determined by negative biomedical factors, but also by the pleasures and gratifications it provides. For that reason, it seeks to balance the benefits and the risks of use, based on the premise that zero risk does not exist. Instead of promoting total abstinence, it focuses on providing reliable and contrasted information, founded on pedagogic processes that enable individuals to make responsible decisions. This innovative approach focuses on the promotion of health and well-being instead of the simple prohibition or stigmatisation of drug use.

In this context of transition towards more comprehensive models, it becomes evident that the way we conceptualise the addictions needs to be rethought. Traditional approaches, centred on a risk and legality binary, tend to reduce such a complex phenomenon to a mere dichotomy between good and evil, concepts sustained on Western regulations that include some deeply rooted ideologies (Zuluaga, 2024). In this sense, models that integrate the psychosocial dimension, such as pleasure and risk management, offer a more nuanced vision that recognises both the benefits and dangers of use, opening the door to a more contextualised and less moralising approach.

The medicalisation of addictions: a process that justifies control

To understand the process by which addictions turned into a problem that legitimises punitive and control policies, it is very important to analyse the role played by the process of medicalisation. From the 19th century, addictions ceased to be seen as a phenomenon managed by people and communities to become an object of study and treatment of medicine:

● The medicalisation and the logic of control. The medicalisation of addictions was based on the idea that drug use was a problem that required treatment and control. However, this logic also justified the prohibition and punishment of drug use, with the argument that drugs cause harm to individuals to legitimise punitive actions. This dynamic led to the emergence of an informal market that economically benefited certain sectors, which ultimately came to control that trade.

● The reduction of the drug phenomenon to a problem. The medicalisation and the logic of control reduced the drug phenomenon to a problem that should be eradicated. This cemented a logic of social and moral control that persists to this day. Prohibition and sanction of drug use became the main strategy to tackle the problem, instead of searching for more comprehensive and understanding solutions.

● The persistence of the logic of control. The control-based logic was established in the 19th century and continues to be dominant nowadays, despite the evidence suggests that these policies are not effective in reducing either the use or the associated harm. It is essential to reconsider this logic and seek more comprehensive and understanding solutions to address the complex phenomenon of addictions.

To approach addictions more accurately, we propose abandoning the conception of drugs as a problem and instead adopting the term ‘issue’. The former implies focusing on the failure to achieve an expected outcome, such as the eradication of the use, thereby limiting the understanding of the phenomenon to a simple success or failure. Instead of that, we propose the understanding of drugs as a whole of interrelated phenomena, which enables the theorisation, research, and formulation of hypotheses regarding its causes, effects, and potential approaches to address them. This point of view, being more open and adaptable, encourages a critical perspective grounded in objectivity and questioning, avoiding reductionist answers and fostering a richer and more context-sensitive understanding of the phenomenon.

From ‘problems’ to ‘issue’: a shift in perspective

For Romaní (2004), addictions constitute a psychosocial phenomenon configured by ideological, political, and economic factors. In this context, the use of the notion of ‘problem’ responds to a social construct that, historically, has been characterised by a punitive approach, where substance use is conceived as a criminal offence subject to sanction. This view not only criminalises users but also reinforces structures of control and exclusion. Following Romaní, we can highlight two key moments in this configuration:

● The Opium Wars: Driven by Great Britain and France to sustain the opium trade with China. Although the serious consequences that the massive use of it had over the population, the imposed treaties legalised its trade, consolidating an unequal relationship between the West and China and proving how economic interests prevail over sanitary or social concerns. This episode not only reinforced the association between drugs and conflict, but also established a precedent in the substance regulation, based on political and trade conveniences, and serving as the foundation of prohibitionist discourses and control models focused on criminalisation, depending on who controls production and distribution.

● The prohibitionism in the United States: In parallel, the United States launched its own war on drugs, initially targeting opium. Beyond the internal concerns about its use, this strategy was driven by economic and geopolitical interests due to the weakening of France and the Great Britain, rival powers in its trade. In this context, some substances were used as scapegoats to divert attention from several social and economic problems, such as immigration.

Both events were driven by the ideologies of religious organisations that saw the use of drugs as a regression to the magical and the savage, and linking those who use them with primitive, deviant behaviours and with the African American immigrant population at first, and currently with Latin American communities (Holliman-Lopez, 2025). In this way, a prohibitionist ideology was consolidated, in which the criminal model based on the criminalisation and punishment of drug use becoming the central pillar of its management.

To fully understand the process of constructing addictions as a problem, we must not forget the role played by the process of medicalisation. From the 19th century, addictions ceased to be seen as a phenomenon managed by people and groups to become an object of study and treatment of medicine, based on the damages caused by drug use and on the search for the most appropriate way to treat them (Menéndez, 1984). From this moment, a clear articulation can be seen between prohibition, sanction of drug use, and the potential harm that these cause to individuals, using the notion of danger to legitimate early punitive actions, becoming entangled not only in laws that dehumanise users but also in the people who develop them (Mulcahy and Seear, 2025). This logic fostered the emergence of a black market that enriched the sectors that took control of the trade, reducing the drug phenomenon to a problem that should be eradicated, founding a social and moral logic of control that persists until today (Fernández et al., 2022).

The conceptual revision we propose highlights the need to adopt more comprehensive approaches to address addictions, suggesting that, instead of simply considering them as a problem, we should treat them as a complex issue. This variation promotes:

● A more comprehensive approach: when talking of ‘issue’, we recognise that addictions are not only an individual problem, but also a reflection of broader social, cultural and economic factors. This approach promotes a more nuanced and less simplistic understanding of the phenomenon, which is key to public policies, social perception, and support for users.

● A reference framework for action: This shift in perspective we proposed has meaningful implications on both individual and collective levels. For that reason, and depending on how the addiction issue is defined, a reference framework will be established to guide the actions and decisions of the individuals and institutions. Hence, adopting a more comprehensive and understanding approach is crucial to address such a complex phenomenon.

Embracing this new approach entails focusing on the failure to achieve an expected outcome, such as the eradication of the use, limiting the understanding of the phenomenon to a simple success or failure. Instead of that, we propose the understanding of drugs as a whole of interrelated phenomena, which enables us to theorise, research, and formulate hypotheses about its causes, effects and potential approaches to address them. This broader and flexible approach encourages a critical reflection, based on doubt and objectivity, moving away from simplistic solutions and promoting a deeper and contextualised understanding of the phenomenon, always keeping in mind the experiences of the individuals who use drugs. This situation facilitates the reimagining of new ways to address this health issue (Syvertsen, 2025).

Conclusions

The analysis carried out shows the need to overcome the hegemonic approaches that have dominated the understanding of addictions. Over time, the penal and medical models have contributed to the stigmatisation of people who use drugs, reducing the complexity of this phenomenon to simplistic perspectives. This look has limited the effectiveness of the implemented policies and has hindered the development of strategies more in line with social and cultural reality.

Beyond the pharmacological effects, it is crucial to recognise the role these substances play in daily life and social interactions, avoiding reductionist interpretations that perpetuate exclusionary discourses. So that, it is essential to adopt comprehensive perspectives that take into consideration their social, economic and cultural dimension.

From this perspective, the management of pleasures and risks is presented as a successful alternative that, instead of criminalising or pathologising the use, aims to minimise harm and provide tools that enable informed decisions. In this context, initiatives such as Energy Control have proved its efficacy, offering objective information and promoting a more conscious and safer relationship with substances.

This is why drug use, rather than being seen as a problem to be eradicated, should be addressed as an issue that requires responses tailored to its complexity. A precision in terminology, along with the overcoming of punitive and moralising approaches, will make it possible to advance towards more effective interventions, grounded in scientific evidence and respect for human rights.

Bibliography

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). DSM-IV-TR. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales. Masson S.A.

Apud, I. and Romaní, O. (2016). La encrucijada de la adicción. Distintos modelos en el estudio de la drogodependencia. Health and addictions: salud y drogas, 16(2), 115-125. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v16i2.267

Bandura, A. (1987). Pensamiento y acción. Fundamentos sociales. Martínez Roca.

Comas, D. (1985). El uso de drogas en la juventud. Instituto de la Juventud.

Comas, D. (2010). Modelos de intervención en adicciones: La lógica de las políticas sobre drogas. Revista Proyecto Hombre, 72, 15-21.

Escohotado, A. (1994). Las drogas. De los orígenes a la prohibición. Alianza Cien.

Escohotado, A. (1997). La prohibición: principios y consecuencias. En Melo, M. and Seibel, S. (eds.), Drogas, hegemonía do cinismo (pp. 38-52). Fundação Memorial da América Latina.

Escohotado, A. (1999). Historia general de las drogas (Vol. 1). Espasa Calpe.

Fericgla, J. (2000). El arduo problema de la terminología. Cultura y Droga, 5, 3-20. http://vip.ucaldas.edu.co/culturaydroga/downloads/CulturayDroga19_Completa.pdf

Fernández, D., Gallego, E., and de la Vega, B. (2022). Energy Control: Reflexiones teóricas sobre un programa español de reducción de riesgos, desde el paradigma de la biopolítica. Cultura y Droga, 27(33), 42-61. https://doi.org/10.17151/culdr.2022.27.33

Fernández, D., Navarro, J., Vidal, C., and de la Vega, B. (2024). Energy Control: más de 25 años rompiendo con la prohibición del consumo de drogas. Revista Internacional de Educación y Análisis Social Crítico Mañé, Ferrer & Swartz, 2(1), 204-249. https://doi.org/10.51896/easc.v2i1.542

Fraser, S. (2024). “Staying with the Trouble” in Ontopolitical Research on Drugs: Keynote presentation delivered at the 2023 Contemporary Drug Problems Conference, Paris. Contemporary Drug Problems, 52(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509231220685

Freud, S. (1974). Uber Coca. En Byck, R. (Ed.), Cocaine papers (pp. 155-161). Stonehill.

Fundación por un Mundo Libre de Drogas. (2025). La cocaína: Una breve historia [Video]. https://www.vidasindrogas.org/drugfacts/cocaine/a-short-history.html

Heinich, R. (1975). Tecnología y administración de la enseñanza. Trillas.

Hernández, R., Fernández, C. and Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación (6.ª ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Herrero, S. (2019). La farmacología del cuidado: Una aproximación deductiva cuidadológica desde el paradigma de la salud y el modelo de Avedis Donabedian. Ene. Revista de Enfermería, 13(4), 1-22. https://www.ene-enfermeria.org/ojs/index.php/ENE/article/view/1087

Holliman-Lopez, G. (2025). Book Review: Narcomedia by Jason Ruiz. Television & New Media, 1, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764251326070

Kahn, E. J. (1960). La Gran Bebida: La Historia de Coca-Cola. Random House.

Kiepek, N. (2024). Discursively Embedded Institutionalized Stigma in Canadian Judicial Decisions. Contemporary Drug Problems, 52(1), 82-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509241269439

Kramer, J. F. y Cameron, D. C. (1975). Manual sobre dependencia de las drogas. Organización Mundial de la Salud.

Koob, G. F. and Volkow, N. D. (2010). Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 217-238. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.110

Kuhn, T. (1992). Estructura de las revoluciones científicas. F.C.E.

Lewin, L. (2009). Phantastica: drogas narcóticas y estimulantes. Amargord.

Ley 5/2002, de 27 de junio, de medidas de protección de la salud de las personas en relación con el consumo de productos de tabaco. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 176, 27225-27244. https://www.boe.es/eli/es-md/l/2002/06/27/5

Mauss, M. (2010). El ensayo sobre el don: Forma y razón del intercambio en las sociedades arcaicas. Katz.

Menéndez, E. L. (1984). El modelo médico hegemónico: Transacciones y alternativas hacia una fundamentación teórica del modelo de autoatención en la salud. Arxiu d'Etnografia de Catalunya, (3), 83-119. https://revistes.urv.cat/index.php/aec/article/download/850/825/0

Menéndez, E. L. and Di Pardo, R. B. (2004). Dependencias y políticas: Los usos técnico/ideológicos del sector salud. Monografías Humanitas, 5, 7-21.

Pallarés, J. (1996). El placer del escorpión. Antropología de la heroína y los yonquis. ZINB Milenio.

Martínez, D. P. and Pallarés, J. (coords.). (2013). De riesgos y placeres: Manual para entender las drogas. Milenio. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/libro/656489.pdf

Mulcahy, S. and Seear, K. (2025). Are We Human Or are We Dancer?: Sex, Drugs, and Bodies of Law. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 1, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2025.2461310

Organización Mundial de la Salud. (1966). Principios aplicables al estudio preclínico de la inocuidad de los medicamentos: Informe [de un Grupo Científico de la OMS, Ginebra, 21-26 de marzo de 1966]. Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/38093

Organización Mundial de la Salud. (1970). Comité de Expertos de la OMS en farmacodependencia [se reunió en Ginebra del 25 al 30 de agosto de 1969]: 17º informe. Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/38263

Pinzón, C. (2023). Prevención de riesgos y reducción de daños: Abordaje, conceptos y estrategias. Centro de Estudios sobre Seguridad y Drogas. Facultad de Economía. Universidad de Los Andes. Colombia. https://doi.org/10.57784/1992/74165

Pons, X. (2008). Modelos interpretativos del consumo de drogas. Polis: Investigación y Análisis Sociopolítico y Psicosocial, 4(2), 157-186. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72611519006

Real Decreto 1/2015, de 24 de julio, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley de garantías y uso racional de los medicamentos y productos sanitarios. Boletín Oficial del Estado. https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2006/BOE-A-2006-13554-consolidado.pdf

Romaní, O. (2004). Las drogas. Sueños y razones. Ariel.

Santos, R. V., Pontes, A. L. and Coimbra Jr., C. E. A. (2020). Um “fato social total”: COVID-19 e povos indígenas no Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(10), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00268220

Syvertsen, J. (2025). Solidarity. Annals of Anthropological Practice, e70005, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.70005

UNODC. (2024). World drug report 2023. United Nations publication. https://reliefweb.int/attachments/a15b9221-edb6-4878-a554-d5a737fbde7e/WDR_2024_SPI.pdf

Yuni, J., and Urbano, C. (2014). Técnicas para investigar: recursos metodológicos para la preparación de proyectos de investigación. Volumen 2. Editorial Brujas.

Zinberg, N. E. (1984). Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. University Press.

Zuluaga, A. (2024). Investigación ontopolítica sobre el cultivo de coca: Integrando saberes decoloniales y feminismos latinos. Problemas contemporáneos de las drogas, 52(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509241271652