Gilbert Shelton and underground comics as a means of social communication. Critical and libertarian education through comix for adults

Gilbert Shelton y el cómic underground como medio de comunicación social. La educación crítica y libertaria desde los cómix para adultos

Gilbert Shelton e os quadrinhos underground como meio de comunicação social. Educação crítica e libertária através de histórias em quadrinhos para adultos

José Carmelo Carrasco Santos

Licenciado en Pedagogía (Universidad de Málaga)

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2116-6347

josecarmelocarrascosantos@gmail.com

Abstract

The emergence of underground comics, in the 1960s, in American society, was transformative for the comics industry itself. It marked the opening of the comics to adult audiences, and the creation of new types of comics with content that, through satire and humor, criticized the surrounding social reality with radical proposals that broke with the Comic Code: pacifist protest, the hippie movement, drugs, opposition to all forms of power (the government, the Pope and the police), and free love, among others. Not only did circumstances change for readers, artists enjoyed greater freedom of expression and owned their copyrights, unlike working for major publishers. Gilbert Shelton epitomizes one of the most significant examples of the emergence of comics, its evolution, and its rise. He started modestly at university with a university newspaper, continued publishing his own fanzines from his garage, published his own comics in other journals or fanzines, and co-founded the publishing house Rip Off Press.

Keywords: comix, comic underground, underground, counterculture, Gilbert Shelton, Comic Code, hippie, education, critical thinking.

Resumen

La aparición del cómic underground, o cómix, en los años sesenta en la sociedad estadounidense, fue transformadora para la propia industria del cómic. Supuso el aperturismo del medio a audiencias adultas, y la creación de nuevos tipos de historietas en contenidos que criticaban, mediante la sátira y el humor, la realidad social circundante, con propuestas radicales rupturistas con el Comic Code: la contestación pacifista, el movimiento hippie, las drogas, la oposición a cualquier forma de poder (el gobierno, el papa y la policía) y el amor libre, entre otros temas. No sólo cambiaron las circunstancias para quienes leían, los/as artistas gozaron de una gran libertad de expresión, y eran propietarios/as de los derechos de autor, a diferencia de lo que les ocurría trabajando para las grandes editoriales. Gilbert Shelton es la personificación de uno de los ejemplos de la aparición del cómix, su evolución y su auge. Comenzó modestamente en la universidad con un periódico universitario, siguió publicando sus propios fanzines desde el garaje de su casa, publicó sus propias historietas en otras revistas o fanzines, y fue cofundador de la editorial Rip Off Press.

Palabras clave: cómix, cómic underground, underground, contracultura, Gilbert Shelton, Comic Code, hippie, educación, pensamiento crítico.

Resumo

O surgimento da banda desenhada underground, na década de 1960, na sociedade americana, foi transformador para a própria indústria da banda desenhada. Marcou a abertura do meio da banda desenhada ao público adulto e a criação de novos tipos de banda desenhada com conteúdos que, através da sátira e do humor, criticavam a realidade social envolvente com propostas radicais que rompiam com o Código da Banda Desenhada: protesto pacifista, movimento hippie, droga, oposição a qualquer forma de poder (o governo, o Papa e a policía), e amor livre, entre outros temas. Não só as circunstâncias mudaram para os leitores, como os artistas passaram a ter maior liberdade de expressão e a deter os seus direitos de autor, ao contrário de trabalharem para grandes editoras. Gilbert Shelton é a personificação de um dos exemplos mais significativos do surgimento da banda desenhada, da sua evolução e ascensão. Começou modestamente na universidade com um jornal universitário, continuou a publicar os seus próprios fanzines na sua garagem, publicou os seus próprios livros de banda desenhada noutras revistas ou fanzines e foi cofundador da editora Rip Off Press.

Palavras-chave: banda desenhada, banda desenhada underground, contracultura, Gilbert Shelton, Comic Code, hippie, educação, pensamento crítico.

Introduction

Censorship has gone through cycles in democratic countries, sometimes lax, other times strict. During the Second World War, and before the advent of television, comics (Coma, 1978) enjoyed their golden age in the United States. Comics featuring heroes and superheroes were aimed at all audiences, both minors and adults serving on the front lines. There were no age recommendations, unlike today's PEGI (Pan European Game Information) recommendations, to give a nearby example. Comics served as political propaganda against the Axis powers, sold war bonds, and raised the country itself as a symbol of freedom. Comics were a faithful reflection of pulp novels (referring to wood pulp that produces a yellowish, improvable paper; popular literature, in short) and their power fantasies, featuring vigilantes fighting crime to impose law and order.

Comics enjoyed popular and governmental favor until a very important event occurred in the 1950s, with the book The Seduction of the Innocents, in 1954, by Fredric Wertham, an American psychiatrist: in his biased research, he suggested that reading comics incited pre-adolescents and adolescents to commit crimes. Crowds burned comics in the streets (Fernández, 2024), mothers holding their children's hands, telling them to throw their comics into the bonfire (these pre-Code comics are highly prized by collectors, the ones that were saved from being burned).

The publishers went to court and had no choice but to submit to the Comic Code Authority, a self-regulatory code that severely limited artists' creativity and, in turn, guaranteed parents that their content was intended for children. The publisher most affected was EC Comics (Entertaining Comics), which had to close most of its crime and horror titles. However, they achieved great success with their comic book, MAD, which was rebranded as a magazine in 1955 to avoid the Comic Code seal. This magazine influenced many children and teenagers, who later became authors of underground comics, or comix.

Censorship of comics was strict from 1955 until the mid-1960s. The generational differences between the Silent Generation and the Boomer generation were most palpable with the hippie movement, the pacifist demonstrations against the Vietnam War, and the rebellion against the authorities. A fruit of this youthful rebellion and nonconformity, underground comics, or comix, were a means of artistic expression with radical content that opposed the imposition of the Comic Code and its ironclad control. Gilbert Shelton is one of the most recognized figures in comics and the counterculture.

Gilbert Shelton, one of the fathers of the American underground

Gilbert Shelton (Houston, Texas, 1940) is one of the fathers of American underground comics of the 1960s. A prolific comic book author, he created parodies and satires on a variety of themes present in his work: the Cold War; criticism of capitalism and multinational corporations; criticism of power and all authority (the political class, the Pope, and the police); the defense of drug use for recreational purposes and lifestyles surrounding these; and the glorification of the counterculture (the hippie movement, pacifist protests, communism, anarchism, and sexual freedom) in opposition to mainstream American society.

Shelton is one of the pioneers of the satirical, rebellious, and irreverent graphic novel of the 1960s underground scene. He was part of the group of underground comic book creators and the countercultural phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s. He was influenced by the Beat Generation, which also influenced the hippies, and whose three most popular books were: Howl (1956) by Allen Ginsberg, On the Road (1957) by Jack Kerouac, and Naked Lunch (1959) by William S. Burroughs (Barea, 2017). The common themes in these books were: the rejection of classic American values, drug use, rebellion against the powers that be (religion, politics, police), great sexual freedom, and the study of Eastern philosophy. Taboo subjects for the American establishment and the American way of life of the 1950s gave rise to the Comics Code, a self-regulation code for comics, or censorship, emulating the restrictive rules and censorship of the Hays Code in film (Millos, 2025). The literary movement of the Beat Generation also influenced artists from diverse cultural expressions: musicians, filmmakers, cartoonists, etc.

Before the emergence of underground comics, there was extensive censorship imposed by the US government. In the 1950s, at the height of the witch hunts led by Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy, there was a self-regulation code for comics, a strict censorship called the Comic Code, which I'll elaborate on later.

The opposition to creative censorship was a determining factor and trigger in the construction of Gilbert Shelton's work (2010): The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers which are: Freewheelin' Franklin, Phineas Freak and Fat Freddy Freekowtski; Fat Freddy's Cat; Wonder Wart-Hog, and Not Quite Dead, a homage to the musical group Grateful Dead, for which Gilbert Shelton designed the cover of their album Shakedown Street. All these characters and their comics are a faithful reflection of his critical personality.

This article analyzes the figure of Gilbert Shelton (Cepriá and López, 2016; Jiménez, 2010, 2017) and his context. The following pages explore the influences and references of the comics medium (Arizmendi, 1975) that influenced his work and the author's own life experience, providing a more concise portrait of the artist.

The origin of underground comics.

The first underground comics emerged in the 1920s, which were called Tijuana Bibles, illicit popular comics during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, which depicting popular comics and animation characters, movie celebrities, and other high-profile people, involved in sexual acts or other lewd situations (Bizarro, 2025). Although their influence on the subsequent underground comics scene is rarely explicitly cited by underground comics artists themselves, Art Spiegelman writes that:

[…] tough nobody has been eager to bring it up before, the Tijuana Bibles were the first real comic books in America to do more than merely reprint old newspaper strips, predating by five or ten years the format we´ve now come to think of as comics. In any case, without the Tijuana Bibles there would never have been a Mad magazine […] and without MAD there would never have been any iconoclastic underground comix in the sixties. Looking back from the present, a time simultaneously more liberated and more repressed than the decades that came before, it´s difficult to conjure up the anarchic depth-charge of the Forbidden that those title dirty comics once carried. (Bramlett et al., 2017, p. 34).

Following the study by the aforementioned psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, there were waves of hatred toward comics due to their supposedly harmful effects on American youth. Not only was there hatred to the medium itself, but also to any author who dedicated himself to producing comics, so many of them signed with pseudonyms for fear of reprisals. The Comic Code, imposed by the government and adopted by all publishers, guaranteed that comic book content would not corrupt the morals of children and adolescents. All comics at that time were required to bear the "Comic Code Authority" seal on the cover, for the peace of mind of adult parents and legal guardians.

In the early 1950s, the American public was consumed by the “comics scare”, the idea that comics (especially crime and horror comics) contributed to juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s aforementioned (1954) publication further fueled the fire, and as a result, a special meeting of the Congressional Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was convened to determine the extent to which comics posed a threat to America’s youth. The comics industry fared poorly in court hearings and arraignments due to the resulting unfavorable public opinion and the very real threat of government regulation; the comics industry instituted the Comics Code Authority (CCA) and its Comics Code, a set of moral guidelines that every comic must meet to receive the Comic Code Seal of Approval. Although participation was voluntary, many parents would not purchase (or allow their children to purchase) comics that did not have the CCA seal (Bramlett et al., 2017).

The Comic Code was very limiting for the creative freedom of comic book authors: they could not romanticize crime, all criminals had to be despicable, they could not disrespect authority (police, judges, etc.), in all circumstances good had to triumph over evil, images of excessive violence were prohibited, terrifying creatures such as zombies, werewolves, vampires... could not be drawn, words like "horror" or "terror" could not be written on comic book covers, images of sexual perversion or illicit sexual relations could not be drawn... All these prohibitions later became the style guide for underground or alternative comics.

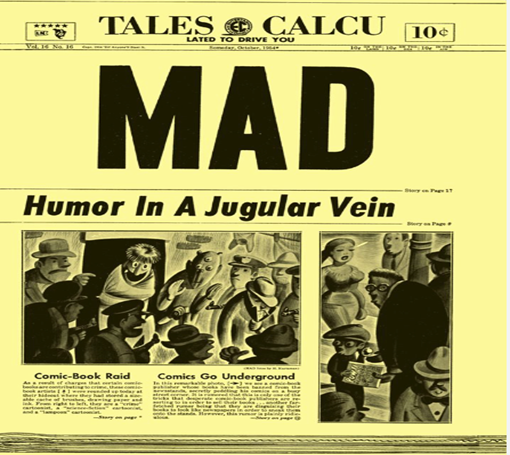

To avoid the Comic Code seal, certain publishers published their own magazines clearly aimed at an adult audience. The pioneer in this regard was MAD magazine (see Figure 1), published by EC, the only one to survive the mass cancellations of EC's horror comics titles:

Issue Nº16 of the comic book MAD came out in 1954 with a prophetic cover: Men in white coats carry one of the cartoonists, Bill Elder, from the street, while Harvey Kurtzman-The cover artist himself- sells his comic books hiding in a street corner. The cover reads in screaming letters: “COMICS GO UNDERGROUND!” (Arffman, 2019, p. 169).

Figure 1.

Cover of the October 1954 MAD comic, comics go underground.

Note. ã Source: MAD Magazine, 16(16). October 1954. The term "underground" was coined. In 1955, Mad, published by editor William Gaines, became a magazine to avoid regulation by the Comic Code Authority. It was published without this seal on its cover, implying that it was not intended for children.

In order to escape the Comic Code Authority, the comic Mad, which began publication in 1952, became a magazine in 1955, by decision of the publisher EC (Entertaining Comics). This change meant that, as a magazine, it was no longer aimed at children, but rather its new target audience was adults. Therefore, it no longer bore the Comic Code Authority seal on its cover. This fact, moreover, no longer limited the creativity of its authors. EC, the publisher most affected by the Congressional Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, was forced to close most of its horror and crime comics titles. Its science fiction comics line continued to be published, but was subject to the creative limitations imposed by the Comic Code Authority. The freedom of expression in Mad magazine influenced a multitude of underground authors in their own work...

Kurtzman´s prediction that edgy comics would soon be produced outside a highly regulated industry soon proved all too correct. The comics industry´s capitulation to the Comics Code, established in 1954, resulted in extremely tight censorship for comics creators. (Arffman, 2019, p. 169).

The rejection of comics as a result of the imposition of the Comic Code was evident in the industry. The number of comics published dropped dramatically, from 500 titles in 1952 to 300 in 1955 (Arffman, 2019). As Natalia Meléndez Malavé states:

The history of reprisals against the freedom of expression of cartoonists and media executives with a satirical bent or those that include cartoon sections is as disastrous as it is extensive. The unique techniques that graphic humor or comics can employ to critique and ignite citizens´ awareness of injustice have too often been the target of a disproportionate backlash. Whether it comes from a general or specialized periodical, or from magazine or comic book, the cartoon is feared. And it is usually feared by those in power -with particular virulence when that power proves illegitimate-. (Jorge et al., 2006, p. 71).

If comics of the 1940s had previously reflected the patriotic consensus during World War II, and continued through the Cold War, underground comics reflected the rebellious spirit of the new postwar generation and served as a means of expressing their concerns. This was the baby boom generation, a large number of young people who grew up very differently than the previous generation: urbanization, the economic boom, mass consumption… all represented a break from the Great Depression and the lifestyles and values of their parents. Young people formed their own consumer social class with its own problems. (Arffman, 2019).

Countercultural comics have their origins in pacifist protest, which epicenter is often located at the University of Berkeley (…). The term comix is simply due to a desire to differentiate these countercultural comics from those produced in an industrial and commercial context. (Jorge et al., 2006, p. 42).

The counterculture had a great impact not only in the United States, but also in Europe, which meant a revolution (McCloud, 2001). As Román Gubern (1972) states: “In the sixties, the European revolution of adult comics took place, partly as a revenge against the infantile status in which this medium had been subjected since its origins”. (Jorge et al., 2006). Gubern also proclaims:

A new map of the media was formalized, in two decades, whit three major publishing forms: commercial comics (for undifferentiated audiences); avant-garde or experimental comics for adult audiences; and the alternative or countercultural, which cultivated social irreverence, pornography, scatology and ugliness, although its antecedents were as far back as the anarchist Les Pieds Nickelés (1908), which were discouraged at the doors of French churches, although its modern formulation came from the American countercultural comix, with Robert Crumb's Fritz Cat at the forefront. This classification obviously does not exhaust all the options, as we should still refer to “protest comics”, with a more or less explicit political dimension, such as Quino´s Mafalda. Also, as a derivation of avant-garde or experimental comics, some brilliant tendencies of “heroic fantasy” or “sword and sorcery” (Moebius, Richard Corben) developed. Comics were a fundamental means of expression for a whole generation in the USA to show their rejection of the Vietnam War. Or in a more generic way, to the warmongering engendered by a sick system. In fact, comics were the flagship of this countercultural movement and served to express the yearnings, anxieties, aspirations and values of a youth tired of a social, political and economic model that they understood was rooting away. In this way, the young authors intend to move away from the escapist and propagandist comic to transform it into an instrument of radical denunciation and social transformation. (Jorge et al., 2006, p. 14).

The bohemian hippie movement meant a cultural change, which embraced drugs, psychedelic rock, sexual liberation, and new philosophies and lifestyles that stressed individual freedom. Social protest focused on New Leftism, which changed the leftist movement from traditional working-class ideology into a protest movement of young intellectuals. It adopted a broader and individualistic approach to leftist politics, opposing the prevailing establishment in its entirety and fighting for all those who were considered excluded from social and economic power -including not only workers but also students, women, blacks, and the poor-. By the end of the decade, the overall term “counterculture” incorporated a large number of groups from extremes represented by junked hippies and New Leftists to yippies and diggers and other in-betweeners who would combine bohemian and social revolt. Barriers were usually blurred and political and cultural endeavors would more or less merge. (Arffman, 2019, p. 171).

Gilbert Shelton´s artistic career

Shelton studied Social Sciences at the University of Austin, Texas (although he previously studied at other universities, I will focus on the one where he developed his facet as an underground artist). In college he developed his vocation as a cartoonist. He lived at the university with the leaders of the pacifist youth protest: Charlie Haden, Jackie Jackson and Janis Joplin, which motivated him to put aside his studies to dedicate himself with more enthusiasm to the publication of a university newspaper, The Texas Rangers, satirical, iconoclastic and precursor of what would eventually become the underground comics. The newspaper was closed down and those responsible were expelled from the university (Rtve Play, 1984). Shelton already began to publish his first comics in this university newspaper in 1959, and would finish his studies in 1961, although he took several postgraduate courses to obtain extensions and not to join the ranks to avoid being sent to the Vietnam War (Echarri, 2022).

After obtaining his degree, he began working as an editor at a publishing house that published automotive magazines in New York. In this job he would take the opportunity to publish his drawings in print.

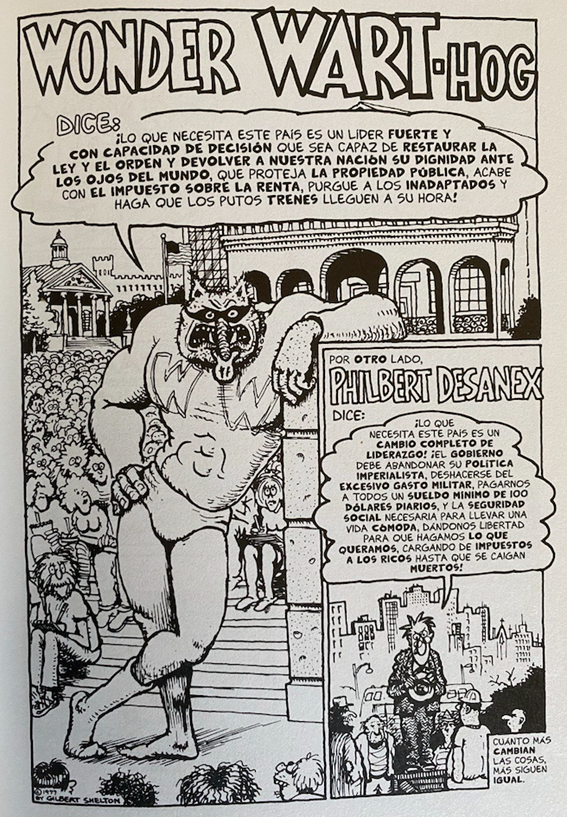

In 1959, he created the character Wonder Wart-Hog, whose comics were published for a time in Bacchanal magazine, a magazine founded by the expelled members of The Texas Rangers. Wonder Wart-Hog is a parody of Superman, and a cruel and brutal satire of all that the values of the American establishment entail; he is a warthog, a fascist and authoritarian anthropomorphic animal. However, his disguise or alter ego, Philbert Desanex, is a progressive whose ideological leanings are close to the new left. Shelton always drew fascists as pigs (see Figure 2). As Chiara Polli writes:

In comics, isotopies can be -and often are- the outcome of semantic coherence among verbal and visual elements, which share some relevant classemes and suggest a homogeneous understanding of these syncretic texts. A brief example of such interplay can be found in (..) taken from one of Shelton´s The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers strips, initially published in 1969. The panel shows a man with a porcine face revealed to be an undercover agent in the story. Here, he is tied up inside a car trunk, displaying the writing “Death to pigs”. In this panel, the isotopy of animality is created by the redundancy of the classeme ‘animality’ in visual (the porcine, chubby face of the policeman with a snout and a feral mouth) and verbal items (the sememe ‘Pigs’ in the slogan “Death to Pigs”). In this respect, the isotopy of animality comes to define -and dehumanize- the political enemy. Such isotopy is fundamental to understanding Shelton´s strip. During the 1960s-70s U. S. counterculture, the derogatory term ‘pig’ was often used to refer to police officers. As a member of this countercultural milieu, Shelton adds slogans such as ‘Death to Pigs’ in his strips and frequently portrays police officers as pigs. (Polli, 2021, pp. 23-24).

Figure 2.

A porcine-looking cop in The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers (Spanish version).

Note. ã Source: Shelton, G. (1989). Los fabulosos Freak Brothers. Obras completas Shelton 1. P. 32, Panels 7-9. Ediciones La Cúpula.

Wonder Wart-Hog had an excellent reception since its appearance, so it was published in different underground or alternative magazines (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Wonder Wart-Hog of conservative political tendency and his alter ego, Philbert Desanex, of progressive political tendency (Spanish version).

Note. ã Source: Shelton, G. (2010). Las mejores historias de: Wonder Wart-Hog. El Superserdo (1978-1999). P. 25. Ediciones La Cúpula (there is a translation error on the part of Ediciones La Cúpula, the Wonder Wart-Hog refers to private property instead of public property according to the original).

In these comics, Shelton already reflected his ideological stance: his attitude in favor of the free consumption of drugs, especially marijuana, the practice of free sexuality, and the rejection of any form of authority or police control.

In 1963 Shelton was drafted into the military, but he claimed to be taking psychedelic drugs, and was exempted. During 1964-1965, he lived with his girlfriend in Cleveland (Ohio), and during this period he tried to find a job as an illustrator at the American Greeting Card Company, a company that printed greeting cards. Another celebrated underground cartoonist, Robert Crumb, worked there, but Shelton was not hired.

In 1966, The Rag, an underground newspaper, began publishing the first comics of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. This underground newspaper glimpsed the birth of the Freak Brothers. Thanks to the Underground Press Syndicate, a network of countercultural newspapers and magazines, the Freak Brothers were published in underground newspapers and comics around the world. The Millar Publishing Company also began publishing the Wonder Wart-Hog, and in 1968 published two quarterly issues with a print run of 140,000 copies per album, but the distributors would not accept them, so only about 40,000 copies of each were sold.

In 1968, Gilbert Shelton moved to San Francisco after having previously worked designing psychedelic posters for a rock venue in Austin, Texas. He began publishing comics by The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers and Wonder Wart-Hog in the pages of his magazine Feds “n” Heads, self-published by Gilbert Shelton himself with a print run of 5,000 copies folded and stapled in his Austin garage. Feds “n” Heads was later acquired by Print Mint, which continued to publish the Freak Brothers comics.

The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers would become the symbol of youth rebellion and hippies. They are three friends or ‘brothers’ whose only concern is to achieve happiness through the consumption of marijuana by living outside social conventions. Their whole life revolves around marijuana and drug use: they want to get a job to spend it on drugs and, when they have no more money, they look for a job again to get money to spend it on drugs. The Freak Brothers' enemy is a narcotics cop, or as they call him in their slang, a narc. This example also serves to differentiate underground comics from alternative comics, when Shelton self-published from his garage, it could be considered a true underground comic: he printed his own run of comics in a copy shop, and Shelton himself was in charge of stapling each issue, distributing it and selling it. However, alternative comics require either a publisher with its own printing house or an external printing house. This publisher also takes care of the distribution of the comic print run by using a distributor, or by being its own distributor.

In 1969, Gilbert Shelton and some partners founded their own publishing house: Rip Off Press (2025). His partners were Jack Jackson, a cartoonist (he signed under the pseudonym Jaxon), the former computer technician Fred Todd, and the resident maniac Fred Moriaty. The four partners call themselves hippies. Rip Off alludes to how comics writers felt about working for a conventional publisher on the traditional commercial circuit, and as a form of protest against their working conditions. En 1969, Gilbert Shelton funda junto a unos socios su propia editorial: Rip Off Press (2025).

The comic book artist who worked for a publishing house was paid a fixed amount per finished page regardless of the time it took to finish it, he worked as a freelancer, any character he created did not belong to him, he belonged to the publishing house so he did not have the intellectual property rights over that character, and the original pages were kept by the publishing house, making it impossible for the author to make a profit by selling them on his own. The alternative or underground publishers had a very different philosophy: those who worked for them saw themselves as partners, so the relationships were more horizontal and not as vertical as in other publishers in the field, the authors still had the intellectual property rights to their own characters, and they still owned their original pages. However, underground authors remained freelancers and, in some cases, were only paid 10% of the cover price for each copy sold, and in other cases -depending on the publisher- they were paid a flat fee per page plus 10% of the cover price per copy sold.

The underground magazine that caused the greatest impact and was the origin of the printing of large print runs was Zap Comix by Robert Crumb, whose first issue was published in November 1967. Underground comics would adopt the final ‘x’ to differentiate themselves from conventional comics with heroes and superheroes, flaunting their rebelliousness and radicalism by dealing with taboo subjects that were unthinkable to see in comics aimed at the general public.

The four partners of Rip Off Press bought a Davidson offset printing press and set up shop in Mowry's Opera House (San Francisco), sharing space with Don Donahue's publisher Apex Novelties, which published Robert Crumb's Zap Comix (1967, 1969). Rip Off Press's first publications were Shelton's Hydrogen Bomb Funnies and reprints of Robert Crumb's April 1964 Comix & Stories.

In 1971, the first collection of Gilbert Shelton's The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comics was published. By then, the company's premises had been destroyed by fire, and they had moved to 1250 17th Street south of Market, at the foot of Potrero Hill. During the 1960s, the company grew and expanded, until it went bankrupt in 1972. The printing staff was laid off, the press was repossessed by creditors, and Rip Off Press became a corporation, with Fred Todd as president, and publishing as its main source of income. The situation began to improve immediately, and in 1979 the high point was reached when Universal Studios paid $250,000 for the rights to a live-action Freak Brothers movie, which unfortunately was never made. Since then, the rights have been negotiated with various parties, and several of them have owned them for some time. To date, no film has been made. However, there is an animated series The Freak Brothers (Shelton, 2020).

Jaxon (who died in 2006) and Moriaty soon returned to Texas, and in 1979 Gilbert Shelton (perhaps overburdened by the intense negotiations prior to the film deal), began what would be the first of several sabbaticals in Europe. Specifically, he moved to Barcelona, to the hippie neighbourhood of La Floresta, together with his colleagues: Nazario, Mariscal, Josep María Berenguer, etc. His comics were published in the magazine El Víbora. Special mention should be made of the comic strip he dedicated to the coup d’état on 23 February 1981 in the special issue of El Víbora dedicated to the coup d'état El Golpe (1981). In 1984, he was interviewed by TVE for the TV show La historieta (Rtve Play), where he stated that:

Superhero comics have always been a bit silly with perhaps the exception of Captain Marvel -author´s note: I assume you mean The Death of Captain Marvel (1982)-. Furry Freak Brothers come from stories sometimes told by my friends, sometimes my own inventions. Freddy´s Cat was originally a real cat living in California. Wonder Wart-Hog comes from ideas sparked by Ronald Reagan.

In 1984, Gilbert Shelton was more interested in the work of his publishing house Rip Off Press than in the search for new cartoonists, without, however, having abandoned the creation of new comics of his characters (see Figure 4); he stated in the aforementioned interview: "Now I'm still doing Furry Freak Brothers and Fat Freddy's Cat. The next Fat Freddy's Cat comic is The Cockroach Wars". In the same programme, Carlos Giménez, Spanish comic book artist and contributor to the programme, would give his opinion on Gilbert Shelton:

Gilbert Shelton is an American cartoonist, he is an underground cartoonist, he has been living in Spain for quite some time. He writes his scripts and naturally draws them. As a screenwriter, he is a man of ideas, a man who can get an idea out of any urban situation. He´s a very talented man, with a large dose of humor, and knows how to make the most of any situation that arises from the world of the high on weed (sic) in search of the daily joint. He is a man of many ideas and a lot of talent. As a cartoonist, his work is a bit in the line of the underground of the 60s, a bit in the style of Crumb. The pen, a bit of pointillism. He started… when he started drawing at the beginning, as a clumsy artist, as an artist with a hard line, with a not very skillful line, and he has had an excellent evolution over the years to become an excellent artist. An example of what I´m saying could be the comic entitled ‘Coup d'état in Spain’ (Golpe de Estado en España), which is a comic where you can see that Shelton draws very well and that he is no longer the man who started out at the beginning. His working material is (sic) very simple: it´s a pencil, a pen and a lot, tremendous amounts of talent and a sense of humour.

Figure 4.

Tejero in one of the panels of Gilbert Shelton's comic strip about 23-F.

Note. ãSource: El Víbora. Issue #2. Special Toda La Verdad Sobre El Golpe. P. 48, Panel 3 (1981).

However, in contrast to Carlos Giménez's opinion -that Robert Crumb influenced Shelton-, according to the Lambiek Comiclopedia website (2025):

He was strongly influenced by Harvey Kurtzman and Willy Murphy.” Gilbert Shelton was uan influence on Ralph Bakshi, Larry Gonick, Krystine Kryttre, Frank Stack y Arthur Suydam. He also found followers in Belgium (Willy Linthout), France (Garf, Pixel Vengeur), Germany (Gerhard Seyfried), the Netherlands (Jos Beekman, Flip Fermin, Frans Hasselaar, Yiri T. Kohl, Oscar De Wit) and the UK (Alan Moore, Stewart Kenneth Moore).

Gilbert Shelton settled permanently in France in 1985, a few months before Rip Off Press had to be moved to smaller premises, with the stock of comics, and surplus equipment, in an inexpensive space in a large warehouse in the Bayview district. In April 1986, it burned to the ground in an explosion caused by a clandestine fireworks factory, resulting in the loss of a seventeen-year accumulation of Rip Off Press's material assets.

Later, Marvel Comics' attempts to improve its bottom line at the expense of the comics industry as a whole resulted, in the mid to late 1990s, in the total collapse of the existing comics distribution system. Again, this was the second time in thirty years that all distributors went bankrupt due to debts owed to Rip Off Press, forcing Todd to seek permanent jobs and reconfigure his comics business. The company had operated out of Todd's old garage since 1999. Regularly scheduled mail-order catalogues continued to be sent out until late 2001, when rising costs and falling sales forced their cancellation. Since then, people without computers can still obtain a printed version of the catalogue (descriptions and prices, but no pictures), which is updated monthly.

Rip Off Press launched its first website in 1996, and in mid-1997 launched its first secure online trading site. The online catalogue has undergone numerous changes over the years, constantly improving. In 2009, the corporation was dissolved, and the Freak Brothers publishing rights reverted to Gilbert Shelton, while the name, website and stock of Rip Off Press, passed to Todd.

Comix style

In the comics, the limitations imposed by censorship rules were broken. The comic code forbade lust, profanity, obscenity, vulgarity, and all scenes of terror, excessive bloodshed, sadism and masochism. Comix exhibited depravity in all its forms. If the comic code demanded that, wherever possible, good grammar be used (Gasca and Gubern, 1991), the comic focused on colloquial street language and slang, including swear words (Barbieri, 1993). The radical nature of the comix was evident in their titles: Big Ass Comics, Abortion Eve (Lyvely and Sutton, 1973), Amazing Dope Tales (Shaw, 1967), Bizarre Sex, Mean Bitch Thrills, Tits “n” Clits Comix, Slow Death Funnies, and Young Lust (Arffman, 2019).

The comix were not only radical in their lack of inhibition, they distanced themselves from the light-hearted adventure and humor of commercial comics by going in other directions, satire, parody and macabre black humor. There were underground versions that mocked the heroes, and the innocent perspective of conventional comics. Superheroes and cute anthropomorphic animals, such as Shelton's Wonder Wart-Hog, or Crumb's Fritz the cat, were parodied with bad slapstick in the comix. In some cases, and quite often, they would use well-known existing characters and give them a twist, taking them to underground terrain. Gilbert Shelton, to give a couple of examples, turned Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy into Little Orphan Amphetamine, and Tricky Prickears (Arffman, 2019).

In general, the liberation of underground comics from the control of mainstream publishers and the comics code gave rise to a great diversity in both subject matter and artistic expression. Drawing styles ranged from amateur to professional; genres from realism to science fiction and fantasy; humor could range from toilet and/or racy sex to serious criticism of society, or deep self-criticism. Unlike commercial comics which were usually in full color, comics were in black and white, due to the cost savings over publishing them in full color (Arffman, 2019).

As for the contents of the comix themselves and their radical subject matter, they were in line and in harmony with the rebellion of the sixties. They had complete freedom of expression to attack the dominant culture in all its spheres. The comix represented the protest of various counter-cultural movements. Anti-authoritarian movements that opposed popes, police officers and presidents, movements against traditional values, pacifist anti-war protest movements, movements against the threat of atomic bombs and movements in favor of ecology. They freely expressed the key ideas of the counterculture: drug culture, radical politics, the hippie movement, the new left, sexual liberation, feminism, occultism, environmentalism and peace movements (Arffman, 2019).

For all their radicalism, the comix protests were based on satirical humor and parody. Most of the time without specific political or ideological commitments. Artists demanded social change that, far from propaganda, used humour to overthrow the dominant ideology (Arffman, 2019).

Comix production and distribution

Opinions differ as to which comic strip appeared first. Broadly speaking, three are usually mentioned: The adventures of Jesus, drawn by Frank Stack under the pseudonym Foolbert Sturgeon. The initials F. S. match (Frank Stack and Foolbert Sturgeon). This comic strip was persecuted as blasphemous, hence the use of pseudonym (Texas is one of the Bible Belt states), and published in 1962 by Gilbert Shelton (Alchetron, 2024). God Nose, made and published by Jack Jackson (under the pseudonym Jaxon) in 1964 (Fox, 2013); and Lenny of Laredo -based on the controversial stand-up comedian Lenny Bruce who made fun of Ku Klux Klan or abortion- by Joel Beck, published by Sunbury Productions in 1965. Few comix were published in the early and mid-1960s. Of the three comix mentioned above, all had the common denominator that they were published and distributed on college campuses as fanzines or college magazines.

Comix or underground comics were usually self-published on a small scale, either by the author himself, like the example I mentioned earlier of Gilbert Shelton's Feds “n” Heads, in his garage at home, or by a small, flexible and unconventional independent publishing house. Unlike the big publishing houses with their authoritarian management and vertical boss-subordinate relationship, the underground authors enjoyed total freedom of expression and were considered co-partners, many of them being founders or co-founders of the publishing house. Another big difference between the mainstream publishers and the small underground publishers was that in the latter case, the authors retained the copyright and the originals. This change meant a greater appreciation of the artist in the underground publishers. In addition, in commercial comics the working groups involved a larger number of people: cartoonists, writers, inkers and letterers, while in underground comics authors worked either alone or in pairs, cartoonist and writer (Arffman, 2019).

Another difference between comics and comixes is that, in the first case, the series could be produced by different artists from issue to issue, and in the case of the comix, the underground authors continued with the characters they had created. Therefore, the comix were more personal creations both in style, in the new attitude towards copyright, and in artistic freedom.

Comic book publishing was a passionate, often discontinued and short-lived activity. According to Jay Kennedy's The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide (1982), there were around three hundred publishers of underground and alternative comics between 1962 and 1974, but fewer than a dozen managed to pass the ten-issue milestone. More than two-thirds of the publishers launched only one comic, although they often optimistically included ‘Issue 1’ in their title. In all, some 800 underground comics were published during this period. La publicación de cómix fue una actividad apasionada, muchas veces descontinuada y de corta duración.

Five underground publishers stand out above all others: Print Mint, Rip Off Press, San Francisco Comic Book Company, Kitchen Sink Press/Krupp Comic Works and Last Gasp. The most important was Print Mint in Berkeley, founded by Don Schenker. Originally a poster shop, Print Mint published its first comic, a reprint of Joel Beck's Lenny of Laredo, in 1966. Larger-scale publishing activity began in 1968 with the satirical newspaper Yellow Dog. That same year, Print Mint began publishing the Zap Comix series with Don Don Donahue's Apex Novelties. By the end of 1974, it had published around a hundred different titles and issues, while the number of publications by the other four publishers ranged from forty to sixty. Such was the success of comic publishing that it became the core of the Print Mint company (Arffman, 2019).

Between 1968 and 1969, comix reached their peak. In 1969, Rip Off Press (co-founded by Jack Jackson -Jaxon-, Gilbert Shelton, Fred Todd and Dave Moriaty in San Francisco) was created. Rip Off Press also produced merchandising items in addition to comix, such as posters and T-shirts. This extra source of income helped fund the production of comix (Arffman, 2019).

Although comix were published all over the United States, most activity was concentrated in the big cities, especially Berkeley and San Francisco. Nearly half of all comix titles and issues were published in these two cities. Other cities with a strong comix presence were Chicago, Austin, New York and Milwaukee. Both New York and Milwaukee were the most important publishing sites after California (Arffman, 2019).

Some comic book publishers had their own stores, like Print Mint, San Francisco Comic Book Company, and Krupp Comic Works...

However, the most important distribution channels for underground comics were the so-called head shops, which specialized in all kinds of hippie paraphernalia: flutes, bongos, psychedelic posters, occult material, underground magazines, etc. Many underground comics could also be ordered by mail and were sometimes sold on the street. Underground comics were also published in the pages of underground newspapers and magazines, such as the East Village Other in New York and the Berkeley Barb and Los Angeles Free Press in California. During the 1970s, more and more comic book specialty stores began to appear, offering a new distribution channel for underground comics as well. (Arffman, 2019).

Even with wide distribution, the comix did not lose their countercultural edge. There weren't many comix publishers, so they never really became, or were seen as, a mass-market product. Publications were concentrated in universities and college towns, which were hotbeds of the 1960s rebellion, and the comics were mainly distributed through specific countercultural channels. This allowed artists and publishers to find their audience and distribution within their own countercultural circles, letting them bypass advertising companies and their rules, including artist control, and keep their copyrights while avoiding the Comic Code (Arffman, 2019).

The rise of experimental and independent underground comics blurred the lines between art and popular culture at the time, influencing other media like music, with new experimental rock 'n' roll formulas such as psychedelic and progressive rock, and folk rock. The film industry began experimenting with new approaches to satire, realism, and criticism; television started featuring sitcoms that broke from convention. Television also tackled controversial topics of the era: abortion, homosexuality, feminism, racism, civil rights, and radical politics. A new, pluralistic postmodern era was developing, and the grand "isms" and ideologies were replaced by eclecticism, irony, parody, pop, camp, gonzo, and kitsch. The boundary between art and popular culture was becoming less relevant. As underground cartoonist Jaxon puts it: "To me, comics are just one aspect of art. You choose the medium that best expresses what you have to say, right?" (Arffman, 2019, p. 183).

The economy of comix publishers

From 1969 to 1972, the annual number of underground comics grew quite a bit, and they started to pique the interest of even mainstream publishers. In 1968, Viking published an album called R. Crumb's Head Comix, and in 1974-75 Marvel put out a series called Comix Book... With the animated film Fritz the Cat, produced by Warner Brothers in 1972, underground comics even made it to the big screen (Arffman, 2019).

Despite these facts, the comix never became a mass-market product. Nevertheless, it reflects the rapid expansion of counterculture into a fashion trend. Different economic sectors saw counterculture as a way to open new markets aimed at young people. Rebellious rock music was adapted to please the general public, hippie clothing entered fashion boutiques, and street vendors traded in hippie items such as psychedelic t-shirts, peace and love badges, and bracelets (Arffman, 2019).

Underground cartoonists were worried about the counterculture turning into a fleeting trend. Everyone talked about not selling out. Zap Comix was offered national distribution but turned it down. When their work fell into the hands of mainstream businesses, artists faced issues with censorship and copyright. For instance, in 1970, an album called GungHo was published in the Netherlands without permission, featuring over two hundred pages of underground artists' work. Viking Press censored some words in Crumb's comics and covered up nudity with black bars. Crumb's work was heavily exploited commercially, with widespread piracy on merchandise like t-shirts, postcards, buttons, and mugs (Arffman, 2019).

Robert Crumb was so disgusted by the movie Fritz the Cat and its 1974 sequel, that he demanded his name be removed from the credits of the first film. Crumb created a comic strip called Fritz the Cat in Hollywood, where Fritz becomes vain and sacrifices his idealism for commercialism. Crumb then killed off the character in this comic (Arffman, 2019).

For fear of commercial exploitation, underground cartoonists began to protect their copyrights more carefully and even suspected their own underground publishers of profit seeking and unfair royalty payments. Disagreements between publishers and artists resulted in a situation where several cartoonists their own publishing houses, such as Kitchen Sink Press and Rip Off Press – “to rip off more of the profits for the artists,” as Gilbert Shelton explained the choice of a name-. (Arffman, 2019, p. 185).

Artists even formed their own unions to protect their copyrights, like Cartoon Workers of the World and United Cartoon Workers of America. However, these were short-lived and ineffective due to the disorganized nature of the underground scene.

Most underground artists were freelancers who were paid royalties, typically ten percent of the cover price. Sometimes, artists received a flat fee per finished page.

Given the constant lack of money among underground artists, it was common for them to juggle multiple jobs unrelated to their art to make ends meet. Jay Lynch, for instance, had to work as a commercial artist, in hospitality, and as clerk in a shoe store.

Conclusions

The rise of comix lagged behind the general countercultural trend. The peak year for comix production was 1972, with over two hundred titles. In the sixties, rebels clashed with authorities: raids, arrests, and police violence fostered an atmosphere of fear, hostility, and cynicism among the "love generation." Rampant drug culture exacerbated problems with addiction, crime, mental health issues, and drug-related deaths. The severity of these issues fractured the counterculture's solidarity and optimism about making the world a better place. All of this led to a division into discordant groups (Arffman, 2019).

The counterculture started losing its radical edge, with protests gradually diluted, as they were absorbed into mainstream culture. The widespread "flower power" movement challenged the rebellious counterculture's stance against consumer society. This shift from rebellion to mass trend, combined with the crises of the 1970s (the Vietnam War defeat, the Watergate scandal, and the energy crisis), led even the non-rebellious, general public to oppose government policies (Arffman, 2019).

Underground comics responded by attacking both the values and institutions of mainstream society and the counterculture itself. They satirically attacked both the warmongering government bombing Vietnam and the idealists with their "peace and love," along with the flower power trend (Arffman, 2019).

The gradual disappearance of the counterculture contributed to the decline in readership of underground comics, jeopardizing their financial viability. Overproduction of comics and rising costs due to increased paper prices, coupled with censorship enacted in 1973, made things worse. Playboy and Playgirl magazines were banned in several states. The film Last Tango in Paris was banned in Salt Lake City. And in the world of comix, Crumb was convicted in New York in 1973 for his comic strip Joe Blow, which contained panels with incestuous scenes (this strip was published in Zap Comix issue #4 in 1969) (Arffman, 2019).

The collapse, brought on by both the psychological blow of censorship and the economic crisis, led to a sharp decline in publications shortly after 1972. From over two hundred titles published, the number dropped to one hundred and fifty in 1973, and further to one hundred in 1974. Despite this, the underground comix scene transcended its own niche, influencing mainstream comics. Conventional comics began tackling a wide range of themes, including environmental protection, women's liberation, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War (Arffman, 2019).

Underground comix marked a turning point where comics shed their naive innocence. It was the transition from comics for children and general audiences to comics for adults, and as some covers proclaimed, "Comix for Intellectual Adults." Underground comix introduced new themes aimed at an adult audience and served as a way for authors to express their personal dissenting opinions, as well as a means to experiment with new narrative forms not bound by conventional comic clichés. They challenged censorship, prevailing values, traditional working methods, and the abuses of major publishers. They knew how to defend their copyrights and create their own industry.

In the specific case of Gilbert Shelton (Rtve, 2013), his mark is evident in each of his comic strips. He spoke out against fascism, authoritarianism, multinational corporations, police control, wars, nuclear weapons, political power, Nixon, Reagan, Tejero's coup d'état – isn't that true critical education and for a better world? – and in favor of the free use of drugs, the hippie movement, the pacifist movement, environmentalism, free love... always using humor as a tool to exercise his critical judgment.

Bibliography

Alchetron. (19 September 2024). Frank Stack. Alchetron. https://alchetron.com/Frank-Stack

Arffman, P. (2019). Comics from the Underground: Publishing Revolutionary Comic Books in the 1960s and Early 1970s. The Journal of Popular Culture, 52(1), 169-198. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12763

Arizmendi, M. (1975). El cómic. Editorial Planeta.

Barbieri, D. (1993). Los lenguajes del cómic. Ed. Paidós.

Barea, F. (2017). Déjalo Beat. Cuaderno de la BN, (4), 12-15. https://www.bn.gov.ar/micrositios/admin_assets/issues/files/c21d0c7d3826a9843731eb622093dbde.pdf

Beck, J. (1965). Lenny of Laredo. Sunbury Productions.

Big Ass Comics. (1969). Big Ass Comics #1. Rip Off Press. https://comixjoint.com/bigasscomics1-1st.html

Bizarro, D. (2 April 2025). Mantener fuera del alcance de los niños: el irreverente mundo de las Biblias de Tijuana. Agente Provocador. https://www.agenteprovocador.es/publicaciones/las-biblias-de-tijuana-9twrt

Bramlett, F., Cook, R. T. and Meskin, A. (2017). The Routledge companion to comics. Routledge.

Burroughs, W. S. (1959). Naked Lunch. Grove Press, Inc.

Cepriá, F. y López, F. (2016). Gilbert Shelton. Historietista / autor / dibujante / portadista / guionista. https://www.tebeosfera.com/autores/shelton_gilbert.html

Coma, J. (1978). Los cómics. Ediciones Guadarrama.

Crumb, R. (1967): Zap Comix #1. Apex Novelties.

Crumb, R. (1969). Joe Blow. Zap Comix, no. 4. Print Mint.

Crumb, R. (1969): Zap Comix #4. Print Mint for Apex Novelties.

Echarri, M. (29 May 2022). “Hedonista, radical y golfo”: Gilbert Shelton, el ‘hippie’ que recaló en Barcelona y hoy triunfa en televisión. El País. https://elpais.com/icon/2022-05-29/la-leyenda-hippie-que-paso-de-vietnam-termino-en-barcelona-y-triunfa-en-la-animacion-de-las-plataformas.html

El Víbora. (1981). El Víbora. Especial #2. Especial toda la verdad sobre el golpe. Ediciones La Cúpula.

Fernández, M. A. (17 March 2024). EEUU: los guardianes de la moral y los perniciosos cómics. LoQueSomos. https://loquesomos.org/eeuu-los-guardianes-de-la-moral-y-los-perniciosos-comics/?cn-reloaded=1

Fox, M. S. (2013). God Nose. https://comixjoint.com/godnose-2nd.html

Gasca, L. y Gubern, R. (1991). El discurso del cómic. Segunda edición. Cátedra. Signo e imagen.

Ginsberg, A. (1956). Howl and other poems. The City Lights Pocket Bookshop.

Gubern, R. (1972). El lenguaje de los cómics. Ediciones Península. Barcelona.

Jiménez, J. (6 May 2010). Gilbert Shelton: “Me tiemblan las manos, estoy pensando en la retirada”. Rtve. https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20100506/gilbert-shelton-tiemblan-manos-estoy-pensando-retirada/330391.shtml

Jiménez, J. (22 May 2017). Gilbert Shelton: “Preparo nuevas páginas de los Freak Brothers para su 50 aniversario”. Rtve. https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20170522/gilbert-shelton-preparo-nuevas-paginas-freak-brothers-para-su-50-aniversario/1550823.shtml

Jorge, A., De La Maya, R. y Cortés, A. (coords.) (2006). Las dimensiones social y política del cómic. Centro de Ediciones de la Diputación de Málaga.

Kennedy, J. (1982). Introduction-Comics, Not Comics. The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide No 1: Listing Alternative Comix in the U.S. & Canada from 1962 to the Present. Boatner Norton.

Kerouac, J. (1957). On the road. The Viking Press.

Lambiek Comiclopedia. (2025). Gilbert Shelton (b. 31 May 1940, USA). https://www.lambiek.net/artists/s/shelton.htm

Lyvely, C. y Sutton, J. (1973). Abortion Eve. Nanny Goat Production. University Park.

McCloud, S. (2001). La revolución de los cómics. Norma.

Millos, N. (19 April 2025). El Código Hays: Censura y rebeldía en la era dorada de Hollywood. ChoheCine. https://chohecine.com/el-codigo-hays-censura-y-rebeldia-en-la-era-dorada-de-hollywood/

Polli, C. (2021). Isotopy as a Tool for the Analysis of Comics in Translation: The Italian “Rip-Off” of Gilbert Shelton´s Freak Brothers. Punctum., International Journal of Semiotics, 7(2), 17-43. https://doi.org/10.18680/hss.2021.0016

Rip Off Press. (2025). About Rip Off Press. https://ripoffpress.com/node/1026.

Rtve. (14 April 2013). Gilbert Shelton, maestro del “underground”: Me levanto pensando en música no en cómics. Rtve. https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20130414/gilbert-shelton-maestro-del-underground-levanto-pensando-musica-no-comics/639361.shtml

Rtve Play. (19 September 1984). La historieta – Cap. 11. `Los aventureros´. Rtve Play. https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/la-historieta/historieta-cap-11-aventureros/2679193/

Shaw, G. (1967). Amazing Dope Tales. The Book Publishing Company.

Shelton, G. (1988). Wonder Wart-Hog and the nurds of November. Rip Off Press.

Shelton, G. (1989). Los fabulosos Freak Brothers. Obras completas Shelton 1. Ediciones La Cúpula.

Shelton, G. (2010). Las mejores historias de: Wonder Wart-Hog. El Superserdo (1978-1999). Ediciones La Cúpula.

Shelton, G. (2020). The Freak Brothers. The Freakin´ History. https://thefreakbrothers.com/pages/history

Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the Innocent. The influence of “horror comics” on today´s youth. Rinehart & Company.