Commodification, Familiarisation and Time: A Comparative Study of Welfare States with a Gender Perspective

Jose Ignacio Torres Romero

Universidad de Málaga, Estado español

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9778-8591

nachoTR@uma.es

Nicolás Ureña Bautista

Universidad de Málaga, Estado español

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3366-6024

nurena@uma.es

Alejandro Granado Bejarano

Universidad de Málaga, Estado español

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-9442-6092

alegrabe98@uma.es

ABSTRACT

The welfare state, a globally adopted political and economic system, presents a diversity of mutually defining welfare regimes, and it is important to understand the relevance of focusing on inequality and the fundamental role of the state in this area. This research approaches such inequalities from a gender perspective, linking decommodification and defamiliarisation as categories of analysis. An international comparison is made by welfare regime, using data from the OECD Better Life Index (2023) and the FOESSA Foundation Report, analysing dimensions of work, contracts, dependency, care and time use. Women perform more unpaid work, resulting as the main axis of inequality that motivates other externalities, developing within welfare states where their support is limited to paid work. The research contributes to the analysis of undesirable social risks in societies, such as the use of time, and their consequences at various stages of life.

Keywords: Welfare state, gender, decommodification, de-familiarisation, de-genderisation, time.

Mercantilización, Familiarización y Tiempo: Estudio comparativo de los Estados de Bienestar con Perspectiva de Género.

RESUMEN

El Estado de bienestar, un sistema político y económico globalmente adoptado, presenta una diversidad de regímenes de bienestar que se definen entre sí, debiéndose entender la relevancia de enfocarnos en la desigualdad y en el rol fundamental del Estado en este ámbito. Esta investigación aborda dichas desigualdades desde una perspectiva de género, uniendo la desmercantilización y la desfamiliarización como categorías de análisis. Se efectúa una comparación internacional por regímenes de bienestar, utilizando datos del Better Life Index de la OCDE (2023), y del Informe de la Fundación FOESSA, analizando dimensiones laborales, contractuales, de dependencia, cuidados y usos del tiempo. Las mujeres realizan más labores no remuneradas, resultando como principal eje de desigualdad que motiva otras externalidades, desarrollándose dentro de unos Estados del bienestar donde su apoyo se limita al trabajo remunerado. La investigación contribuye al análisis de los riesgos sociales no deseados de las sociedades, como el uso del tiempo, y sus consecuencias en diversas etapas vitales.

Palabras clave: Estado de bienestar, género, desmercantilización, desfamililarización, desgenderización, tiempo.

Mercantilizaização, Familiarização e Tempo: Um Estudo Comparativo dos Estados-Providência com uma Perspetiva de Género.

RESUMO

O Estado-Providência, um sistema político e económico adotado a nível mundial, apresenta uma diversidade de regimes de bem-estar social que se definem mutuamente. A importância de focar a desigualdade e o papel fundamental do Estado Providência nesta área é destacada em investigações recentes. Esta investigação aborda estas desigualdades a partir de uma perspetiva de género, reunindo a desmercantilização e a desfamiliarização como categorias de análise, fá-lo através de uma comparação internacional dos regimes de proteção social, utilizando dados do Índice para uma Vida Melhor da OCDE (2023) e do Relatório FOESSA VIII (2019). Analisando as dimensões laboral, contratual, de dependência, de cuidados e de utilização do tempo. As mulheres realizam mais trabalho não remunerado, constituindo o principal eixo de desigualdade que motiva outras externalidades, desenvolvendo-se em Estados-Providência onde o seu apoio se limita ao trabalho remunerado. A investigação contribui para a análise de riscos sociais indesejados nas sociedades, como o uso do tempo e as suas consequências em diferentes fases da vida.

Palavras-chave: Estado de bem-estar social, gênero, desmercadorização, desfamiliarização, desgenderização, tempo.

Introduction

Perfect societies only exist in utopian fictions, although aspiring to them allows us to transform them and lead them towards ideal horizons that channel their dynamics. This paper seeks to be a succinct but revealing example of such "imperfection", revealing the differences that exist between some countries according to their welfare regimes, with gender as the main category of analysis.

International institutions, such as the United Nations, are calling for transformation processes to create a world that is respectful in economic, social and environmental terms: the Sustainable Development Goals. These goals are cross-cutting and intersect with each other; however, in our task, we are guided by the search for gender equality and the reduction of inequalities. Similarly, when we speak of welfare states, it is also necessary to know what welfare is, which can be understood as the satisfaction of material needs carried out by human beings (Morales, 1994). These elements have led us to our research question: how do women live in welfare states?

The issue is motivated by feminist and social critiques of welfare states and how their own structural definitions distribute welfare in an asymmetrical way between genders (Lewis, 1992), reproducing the logics of patriarchal domination and expropriating resources from the female population (Lucas-García & Bayón-Calvo, 2017). Social and scientific awareness of this order of things is what makes it possible to problematise this specific form of inequality, which could even be conceptualised as structural violence[1].

Criticisms of this calibre have a long history and are still relevant in our immediate context, so we will analyse eight countries according to their welfare regime models: liberal [United States and United Kingdom], corporate [Germany and France], social democratic [Denmark and Sweden] (Esping- Andersen, 1993) and Mediterranean [Spain and Italy] (Moreno & Marí-Klose, 2013). A quick glance at global indicators, such as the Gender Inequality Index or the Human Development Index, shows that the situations of equality recognised and promulgated by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are not a manifest reality. Based on the above, we have specifically selected indicators from the OECD's Better Life Index (OECD, 2022, 2023): these secondary sources will serve as a basis for our analysis.

In this research we have seen the strength of the processes of social change in welfare regimes, even though they reveal glaring gender inequalities. We hope that this work will help to raise awareness and critique societies that seek to be more just and humane, yet remain embedded in certain gendered "imperfections".

Theoretical Framework Gender in welfare states

The welfare state should not be understood as an abstract entelechy, but as a network of public institutions that provide society with social services, in order to procure vital improvements and guarantee equal opportunities for citizens (Navarro, 2006). From their historical antecedents, such as the Poor Laws in England in the 15th century or the Social Programmes in Germany in the 19th century,

welfare states have always been legitimised because morally they are the promoters of wellbeing (Doyal & Gough, 1991).

However, this raison d'être would remain subject to an overt and incomplete narrative, in which the definition of welfare states maintained and maintains gender inequalities (Saxonberg, 2012). After the Second World War, its latent dimension could be clearly appreciated, locating that its actions in favour of social justice and welfare were secondary, as the concrete objectives were to motivate the macroeconomic stabilisation of welfare states. Within the Keynesian models, the consolidation of these states allowed, through economic policies, to stimulate domestic demand and the productive expansion of the nations (Mishra, 1992) subscribed to these welfare discourses, maintaining widespread inequalities, by promoting policies aimed at full employment and family support, two of the spaces that reproduce these social aspects (Lucas-García & Bayón-Calvo, 2017).

Contextual particularities are what have allowed the differentiation of social welfare models and, linked to them, different regimes. According to classical analyses we distinguish: liberal, conservative and social democratic; it is the relations between states, families and the economic market that define concrete regimes of "welfare capitalism" (Esping-Andersen, 1993). The basis of these regimes today is the distribution of resources through decommodification and defamiliarisation, understood as processes in which both the market and the family cease to be the providers and main responsible for citizens' welfare and are replaced by state social services (Esping-Andersen, 1993, pp. 41-74). In this context, a scenario of regulation of market practices (Filgueira, 2013) and models of state subsidiarity in favour of families (Calero, 2021) is favoured.

Each of these regimes establishes a system of social stratification linked to different statuses: material (social classes and occupations) and entitlements (rights and duties) (Campana, 2015). However, the interaction of the agents that compose them, in the transit towards the conquest of their well-being, propitiate the production and reproduction of the social stratifications in which they find themselves (Gough & Wood, 2004; Horton & Lynch-Wood, 2023), and with it, their intrinsic inequalities.

T. H. Marshall's own androcentric definition of social citizenship, which underpins welfare states, is a case in point[2]. From a critical perspective, we can see that the gender bias is implicit in the central valuation of contractually regulated jobs (extra-domestic productive-formal activities), making care work invisible as a marginal axis of the well-being of societies and individuals, and even finding similarities at the international level in the unequal distribution of tasks and care (Sagastizabal, 2020; Jiménez, 2020; Manuel, 2016; Ruperti-León, 2019; Campillo & Sola, 2020).

The neglect of feminised social dimensions in welfare regimes is what has historically produced their devaluation through the scarce presence of women in the public sphere (Walby, 2020; Lucas- García & Bayón-Calvo, 2017). It should be mentioned that this appreciation is based on the sexual division of labour, an aspect that helps to explain the different valuation of the private and public spheres, as well as the status associated with the male and female gender (Federici, 2013; Carrasco, 1995).

Not only is it understood in this area, but women have unequal access to support due to institutional barriers to social services (González, 2023; Lucas-García et al., 2022; Estermann et al., 2014). Paradoxically, however, women have massively joined the labour market, equalising labour force participation rates with men, serving, in Spain and other countries, as a "social shock absorber for the shortcomings of public welfare policies" (Moreno, 2010, p. 19). However, the same does not occur when we talk about later stages of labour activity, such as old age (Pérez, 2003).

Alongside this and from leisure and free time, fundamental components of welfare states, there is evidence of disparity in access according to gender and type of welfare system, with women and less developed countries being the most affected in terms of leisure opportunities (Álvarez, 2018). Globalisation and the digital era (Castell, 2000), which gave rise to the Crystal Societies (Acevedo, 2022), are the contexts that have led to technological initiatives to mitigate these inequalities in the field of leisure and time distribution, which could enhance development and equity in less favoured states (Castro et al., 2017). Furthermore, such inequalities affect social inclusion and exclusion in welfare systems because they overlap with structural issues that influence, for example, educational trajectories (Bernárdez-Gómez, 2021) and reveal obstacles in contemporary education systems (Ovejero, 2023).

Comparative studies of welfare states have based their perspectives on family and market factors. The classical view is based on Esping-Andersen's (1993) explanation that family expenditure promotes and indicates the degree of defamiliarisation within welfare regimes, which reduces the "responsibilities" and "services" provided to families by the responsible and constituent subjects of the family. On the basis of this theory, public benefits help to defamiliarise social relations in welfare states, providing actors with independence and economic support. This is complemented by telematic ways of relating to each other, virtual platforms mediate communication and understanding of reality, providing explanations for the social changes linked to gender in welfare regimes (García et al., 2021). In this framework of ideas, the vision of decommodification is inserted, devaluing the imprint of the market to define subjects and complementing it with a status linked to rights: Citizenship (Esping-Andersen, 1993).

In applying these theories as a basis for explaining the data, we have noted a lack of sensitivity to gendered realities, although Esping-Andersen incorporated the ideas of defamiliarisation and decommodification into his theories in response to the criticisms of these same shortcomings that we have noted. However, for the motivations of our work, we assume the importance, when analysing welfare states, that for this research it seems more appropriate to focus on the degrees of degenderisation provided by Saxonberg (2012) in his analysis of welfare states.

It can be observed that the term degenderisation is very present in the policies carried out in recent years, even showing changes over this time, which make visible, in the welfare states, a slow but generally positive change towards equity in care in the different European welfare states (Szelewa & Polakowski, 2023).

The reason for this option is legitimised by what has been observed not only in the tables: the concept of genderdization is the link between the two previous concepts (defamiliarisation and decommodification). Focusing on this issue, we approach a comparative by differentiating between the types of regimes - differentiated by Esping-Andersen - where a common reality is observed in all of them, i.e. gender inequality.

Methodology

Research design

The aim of this paper is to conduct a reflexive and exploratory analysis of the situations shared by populations in different welfare regimes from a gender perspective. Through this work, it is intended to present an initial foray that can be developed in future research projects. The analysis techniques have been descriptive and interpretative, from secondary data sources (Del Canto & Silva, 2013), provided by the Better Life Index, which can be found on the OECD website (selected on the basis of the latest available data), and from the FOESSA VIII report, which provide great information, focusing the review on available social indicators that allow us to compare the different welfare regimes (Sartori & Morlino, 1994). The database has been chosen intentionally, as other databases do not contain as much information to make comparisons with countries outside the European Union that are important for the study of liberal welfare systems, such as the United States and the United Kingdom (Ayos & Pla, 2021). Likewise, the countries selected for the analysis have also been carefully chosen, highlighting those that this team considers most representative of each welfare system, with Sweden and Denmark representing the social democratic one, Germany and France the continental one, and Spain and Italy the Mediterranean one.

In the analyses we consider the gender differences (Cobo, 2005; Espinosa, 2022; Sanjuán et al., 2023; Martínez et al., 2024) existing in the time dedicated to employment, highlighting gaps in the dedication to various tasks that can be linked to subsequent analyses of work-life balance. It should be noted that the conception of gender used is based on a binary conception, as the databases consulted provide data according to this same conception. Research into the structuring of time and its distribution in everyday life (work, unpaid work and housework) of women and men will shed light on the differences and similarities between these human groups (Durán, 1986, 2007, 2008; Miller, 2004).

The observation of the development of the demographic dependency ratio is relevant to show the relationship between the growth of the dependent population and the distribution of care, and within these demographic dynamics and processes, the amount of social resources, in the form of social spending, allocated to family units for the care of these dependent groups (people under 15 years of age on the one hand, and those over 65 on the other, according to the OECD) will be studied.

The types of employment, complementing the uses of time, will ensure an understanding of the extent to which people spend their days between work, household maintenance and care time. Linked to this, analyses of maternity and paternity leave, as well as the aforementioned social expenditure on the family, provide information that helps to cohere the view of the different Welfare States and create a joint perspective of the different contexts.

Table 1.

Indicators, countries and Welfare Regimes.

|

Indicators |

Countries |

Welfare Regime |

|

Dependency ratio (% of active population) |

France |

Continental |

|

Germany |

||

|

Uses of time (male/female) |

Italy |

Mediterranean |

|

Spain |

||

|

Types of contract (Part-time/full-time) |

Denmark |

Social Democrat |

|

Sweden |

||

|

Paid leave (maternity/paternity |

United Kingdom |

Liberal |

|

Public expenditure on families (% of GDP) |

United States |

Source: Own elaboration, based on Esping-Andersen (1993), Del Pino & Rubio (2016) and OECD (2023).

Finally, an effort will be made to make visible, through this structuring, the consequences of the gender gap in non-voluntary early retirement pensions, focusing on the specific case of Spain.

Results

The descriptive analyses shown here wish, succinctly, to represent the reality of people living in the different welfare regimes, applying the gender perspective in this task. The results obtained in the selected indicators are linked to data extracted from the World Values Survey, in the waves 2017- 2022, strategically aiming to expose information that complements, feeding back our analyses from the social discourses collected in the registers promoted by Inglehart (1971).

The structure of the results is divided into two analyses: descriptive and interpretative. Their separation does not make them mutually exclusive; their arrangement clarifies their reading and assimilation. In fact, they will be dealt with jointly in the conclusions, producing in them a reformulation of what has been said in these sections and their link with the theory referred to.

One of the indicators that shows us the situation of societies is the dependency rate (Moragas, 2002; Zaidi, 2008). The demographic contexts of States give rise to highly influential, objectified circumstances, with repercussions on relational dynamics and political-institutional actions (Rafegas, 2021). The dependency ratio itself establishes a relationship between two human groups, dichotomising them into: active population (people between 15-65 years of age) and dependent population (people between 0-14 and those over 65 years of age). The mathematical relationship generated in this rate makes it possible to observe retrospectively and prospectively the population trajectories and how these influenced, influence and will influence the well-being of states, societies and individuals (Cabrero, 2011).

Figure 1 shows a comparative representation of the dependency ratios between the selected countries, indicating the different demographic situations, from which we can extrapolate the different social situations that have given rise to these figures, and in which we can observe the "demographic question". Its importance is defined by the fact that it shows the increase of a large sector of the population that will require certain public policies. These demographic facts will have a different impact depending on each welfare regime, and the ways in which they deal with it through different channels (state, market or family).

Figure 1.

Dependency ratio (percentage of people under 15 and over 65 compared to the total population).

|

Source: Own elaboration, based on OECD (2023) (https://data.oecd.org/pop/old-age-dependency-ratio.htm#indicator-chart).

In Figure 1, we are looking at the increase in the number of people of dependent ages, an increase that occurs irrespective of the welfare system in question, showing a growing need for care for this population. However, we should not only understand the population statistically defined as dependent as non-contributors to welfare. In the dynamics of care, these groups include people who receive care, but who also provide care. They must be understood as human resources of societies that do not tend to be quantified because they occur in the private sphere and in informal terms, although they are indispensable in increasingly less committed welfare states.

It is important to add the impact of different dimensions that intersect with the demographic circumstances mentioned above. One of these is the existing gender relations between contractual statuses in employment, influencing full-time and part-time contracts. In addition, it is essential to look at the different uses of time spent on care (unpaid work) and paid work (paid work, according to the original OECD term). The data coded in these indicators reinforce the care needs and, once again, we will observe where the care task falls regardless of the regime in question.

Public spending on the family should be interpreted as an indicator of the degree of defamiliarisation, explaining an intrinsic logic: the greater the investment in the family, the greater the defamiliarisation. Therefore, in these regimes, greater equality in the insertion of women into the labour market can be observed. In other words, we can interpret a commodification (the axis of the welfare regimes) of the female collective, helping in the economic expansion, but also becoming new axes of inequality-exclusion added to their initial gender situations.

Within this logic, it is assumed that the state's investment in the family, with the aim of supporting the dependent population, is intended to provide aid to alleviate the care burden of this sector of the population. The double meaning of this political-institutional praxis manifests a discourse that seeks to promote the emancipation of both the caregivers (who will be able to devote more time and resources to work) and the recipients of care (who will see their life opportunities increase). On the other hand, these means enable ways for the majority of the population to gain access to greater well- being.

As can be seen in Table 2, the very family-oriented countries, such as those representing the Mediterranean regime, are those that allocate the lowest percentage of GDP to the family. These characteristic reveals that in this regime the role of family solidarity networks is central, giving shape to a particular structuring of its welfare state in relation to the public expenditure allocated. The particularity of Spain, based on its low investment, underlines the importance of familialism in this country (Del Pino & Rubio, 2016). On the other hand, the greatest economic resources allocated to the family are observed in the so-called social democratic regimes, where the role of the state plays a strong defamiliarising function. However, no major differences are found with countries belonging to conservative regimes (France or Germany), where the premise is governed by state intervention whenever the family fails... these data could provide clues to this "failure".

Table 2.

Public expenditure on households (% of GDP).

|

Total public social expenditure on households (% of GDP) |

|

|

France |

3,44 |

|

Germany |

3,24 |

|

Italy |

1,87 |

|

Spain |

1,48 |

|

Denmark |

3,31 |

|

Sweden |

3,42 |

|

United Kingdom |

2,49 |

|

United States |

1,04 |

Source: Own elaboration, based on OECD (Better Life Index) (2023) (https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm).

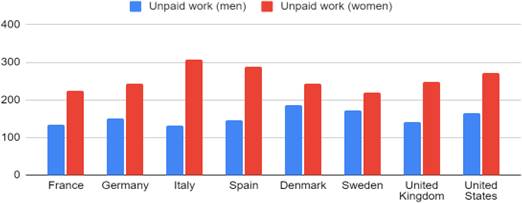

In line with what is described in Table 2 above, in the Mediterranean countries the use of time devoted (Table 3) to unpaid work by women is the highest, coinciding with those countries in which there is less social expenditure on the family. Nevertheless, what can be seen, regardless of the welfare system, is that women are the ones who dedicate the most time to unpaid work, finding in this category the activities related to the area of care; maintaining feminised care.

Table 3.

Use of time spent in paid (and unpaid) work by sex of the working-age population (minutes/day).

|

|

Sex (Age) |

|||

|

Male (15-64 years) |

Female (15-64 years) |

|||

|

Countries |

Paid work or studies |

Unpaid work |

Paid work or studies |

Unpaid work |

|

France |

235 |

135 |

175 |

224 |

|

Germany |

290 |

150 |

205 |

242 |

|

Italy |

221 |

131 |

133 |

306 |

|

Spain |

236 |

146 |

167 |

289 |

|

Denmark |

260 |

186 |

195 |

243 |

|

Sweden |

313 |

171 |

275 |

220 |

|

United Kingdom |

309 |

140 |

216 |

249 |

|

United States |

332 |

166 |

247 |

271 |

Source: Own elaboration, based on OECD (Better Life Index) (2022) (https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54757)

* Use of time (min/day) (1440 min = 24h).

Comparatively between the genders, we find that there is always an inverse relationship: men spend more time on paid work than on unpaid work, and women spend more time on the opposite, which shows that there is an interdependence between the data, distinguishing the distribution of work (paid and unpaid), and creating spheres (public-private) where time is spent in a gender-differentiated manner. In this international homogeneity, there is only one dissonant fact in Sweden. Sweden is the only country in which the time spent by women in paid work exceeds the time spent in unpaid work, which to some extent reinforces the thesis that there is a greater degree of defamiliarisation in social democratic welfare regimes.

However, this is not significant because it does not hold in comparison with Denmark. The consistency of the above statement could be explored in other work, incorporating the processual perspective, and comparisons within the welfare regimes themselves could be made to see the differences in this issue, and to see how gendered categories of welfare states have remained, and how they have progressed in realizing gender equality.

Table 4.

Types of contract over total (part-time - full-time) by gender

|

|

Sex |

|||

|

Man |

Woman |

|||

|

Countries |

Full-time %

|

Part-time %

|

Full-time %

|

Part-time % |

|

France |

69,9 |

7,3 |

71,5 |

19,2 |

|

Germany |

78,2 |

10,4 |

52,4 |

35,7 |

|

Italy |

69,7 |

7,3 |

67,1 |

32,9 |

|

Spain |

70,3 |

6,1 |

76,2 |

19,1 |

|

Denmark |

72,7 |

12,7 |

68,3 |

22,1 |

|

Sweden |

78,9 |

9,4 |

70,8 |

14,6 |

|

United Kingdom |

N.D |

11,8 |

N.D |

32,9 |

|

United States |

77,1 |

N.D |

61,8 |

N.D |

Source: Own elaboration, based on OECD (Better Life Index) (2022) https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54749

*Type of contract (% of total number of contracts)

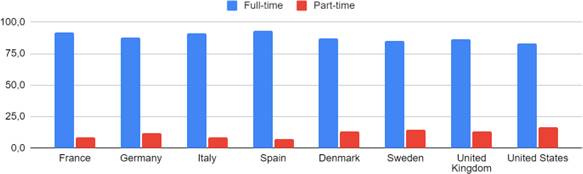

What is most striking in Table 4 is that in the men's group, in no country does the percentage of part-time contract types exceed 14%, while in the women's group, these percentages never fall below 14%. The synthesis of the data in this commentary sheds light on the so-called second shift or double shift of women who, while mostly holding part-time contracts, devote more time to care. Care is understood in a broad sense, not strictly in the aid or support of the most vulnerable-dependent groups, but also in the attention paid to all the activities and processes that define daily and domestic life. The research applies a general vision of care, understanding it as those actions of the human species that involve the maintenance of life and the world in which it develops (Tronto, 2009).

The most unequal data are found in Germany and the United Kingdom, countries that a priori belong to very different welfare regimes, where the degree of commodification is, moreover, usually high. However, this does not seem to be the situation for women in these countries, where only 52.4% of their total contracts are full-time in Germany... It should also be noted that a comparison with the UK is not possible, as there is no data on women's full-time contracts. What these data do not show are total contracts, they show different percentages of totals in each country, making it difficult to analyse underground economies or unpaid work.

Table 5 shows a clear inequality (excluding the US case, where no data are recorded). Irrespective of the type of welfare state regime to which one belongs, there is again a gender- differentiated dynamic, showing possible interdependencies between them. In this case, women are in all cases more likely to have more than three times as many weeks of paid maternity leave as men, in several countries. Such information is illustrative of the different circumstances of men and women in the face of children and work, creating variables that will differentiate their lives in terms of work-life balance. In addition, a hidden reading of these data can be made, allowing for the interpretation of difficulties in achieving full labour market insertion under equal conditions. A noteworthy fact is the equal number of weeks of sick leave in Spain, which again reveals the latent familiarism of Mediterranean welfare regimes, although this statement does not apply to Italy.

Table 5.

Duration of paid parental leave (weeks).

|

|

Sex |

|

|

Countries |

Man |

Woman |

|

France |

31,0 |

42,0 |

|

Germany |

8,7 |

58,0 |

|

Italy |

15,0 |

47,7 |